I’ll probably quote Karen Barad in every one of these posts. I’m reading their book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning right now, and listening and re-listening to their dense, calming talks on YouTube. The snippet above is from “Troubling Time/s and Ecologies of Nothingness: Re-turning, Re-membering, and Facing the Incalculable,” which was first sent to me by my friend Jeremy Geragotelis, who shares with me a deeply felt compulsion to trouble time. With this text, Jeremy introduced me to Barad’s ideas, and I haven’t been the same since.

Barad is a quantum physicist and feminist scholar who writes about “all possible histories,” and the imagining of infinite possibilities for living and dying, “to turn over and over again the soil that gets encrusted on loosening the ghosts that have been forgotten” (from the talk version of the essay above). Embedded in the thickness of Barad’s “time being becoming” is my own wish for a new methodology for working with queer histories/futures, to embed and enfold moments into each other as a way to refuse chrononormativity, to bypass the “linear construction of time that serves the workings of racialized capitalism, imperialism, and colonialism” (Barad).

Which moments to examine? What to make of/from them?

My father recently shared with me a short piece that he wrote about his childhood home on the island of Lesvos, Greece. The text documents his memories of the village of Agia Paraskevi in the 1950s, and it was published in a newsletter that’s edited and distributed to a diasporic community that left the island in waves of migration throughout the 20th century. His original text appears in Greek of course, but I wanted to see what Google Translate would make of it, and it’s kind of remarkable.

He titled his piece “Agia Paraskevi 1950–1960,” but it got cut off when he made a copy for me, with only the word Agia appearing entirely, which means saint or holy in Greek (the village is named for Saint Friday). The rest of the title was sliced in half and illegible, but Google auto-completed it and re-titled the piece “Holy preparation of him.” This is some kind of failure/gift and I’ll take it, this language now traveling through so many layers of mediation, from a Google doc to email to the printed publication to my father’s copy to Google’s translation algorithms, and finally the JPG that I am now posting here to Substack’s servers. This is—and isn’t—about accuracy, and the many possible truths that might be revealed through a close examination, through the intermediary agents, the tools we use to inscribe, to measure, to translate, to communicate, to remember. It can all be considered.

Another failure here, in the actual printed publication, is the misspelling of his name, which appears in Latin letterforms. The third “l” in “Soulellis” is missing and our family name appears as Soulelis. The “elis” or “ellis” ending on family names is typical to Lesvos; both are common (for example, Geragotelis—Jeremy’s family is also from the island). Perhaps the missing “l” is another kind of mediated gift, pointing towards the fluid nature of language and identity when considering place. I like that it refuses fixity; the name is somewhat preserved, but different. It presents something else to consider.

I’m interested in the intermingling of the personal and the political when wandering around archives. I feel this profoundly when I enter queer archives or go about queering archives, sensing my own timeline entangled with something else, much larger, but not always accessible, and never complete. Again and again, trying to locate myself in a queer timeline produces strange sensations for me, sometimes satisfying (oh look, there I am), but often painful (I can’t find myself).

I recently started gathering all of the photographs my family took on our trips to Lesvos earlier in life, pulling them from our photo albums. The first trip was in June 1971, when I was three years old; this was also my mother’s first trip to Greece after marrying my father in 1965, and my father’s first return to the village since leaving in 1961. It was significant in so many ways.

What we have now, as evidence, are ten Polaroid images taken on that trip (four appear in this post). It’s an intimate archive unique to my family, but I’m searching for more, for other kind of entangled meanings that might be found here, beyond the personal. Strategies that I might take with me. I’ve only just started to see them.

This morning, I decided to scan the ten Polaroids with my phone, but I couldn’t avoid the glare. Rather than look for a flatbed scanner, I downloaded Google’s Photoscan app, which uses a unique process to create scans without any glare. You scan each photo 5 times—once in its entirety, and then 4 additional times, each centered on a large circle that the app positions at each of the 4 corners of the image. The software then seamlessly stitches the images together. The results are extremely satisfying, producing the clean JPGs here in this post, if also somewhat unsettling, with a kind of bright, digital-ish sheen applied to what is otherwise a 53-year-old object. I’m not sure if it gives them new life, or deadens them.

One aspect of Polaroids that I love is that each one is a unique object that was present at the original scene (not just a recording of the light; rather, the material substrate itself was there). These Polaroids are different now; I’m fascinated by their sudden shift in appearance, in a new digital state, with all of the failures and gifts that they’ll accumulate, still to be discovered.

Time brings changes, changes create memories, as Google translated the first line of my father’s text, and I’m curious how we might take these very specific material artifacts, the objects and all that they inherit across time, across all of the different apparatuses that produce them, changing along the way, and open them up to the thickness of time in them, unfolding from them. Could this strategy be used to re-shape past events?

Traditional archival strategies might focus on precision and fixity in the construction of accurate timelines, with the intent to fix images like these into a single point, or a series of points; to determine their place in time, and to write the narrative. But what if we were to trouble those archival strategies (or even trouble the archivists themselves, or the entire archive itself for that matter), and “spread” or smear these artifacts out over a larger, interpretive time/space? Can we open up a specific point and expand it out, connect it, entangle it—even touch it?

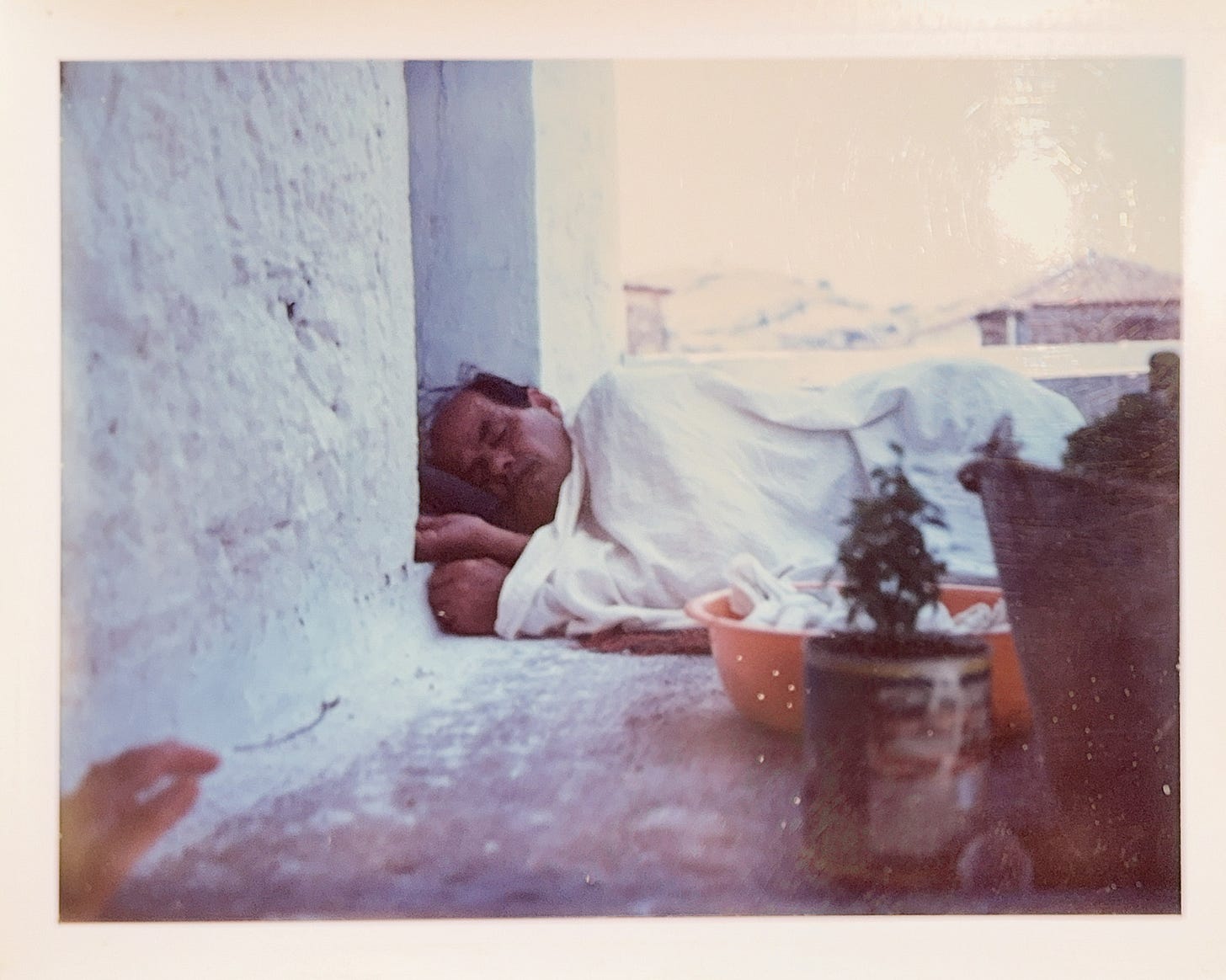

I remember a few blurry things from that trip, like the stray cats in the village, and a feeling of being seen by the village women who would come to visit the house. I also remember how strange I thought it was that my grandfather would sleep outside on the roof when we were there. It seemed radical to my three-year-old self. I think I grew up thinking that he preferred to be out there, in some kind of rebellious way, and I’m sure this contributed to how I grew to think of him. But now I see that it was probably more about the circumstance of our visit; the house was tiny and crowded. My parents and I slept in the one room upstairs, and my grandmother was sleeping in the one room downstairs. My grandfather chose the roof.

I forgot about this photograph, until now. This is the one photo, from the ten that I scanned this morning, where the glare wasn’t eliminated; another kind of failure, visible in the upper right corner. I tried to re-scan it and the failure was repeated, so there’s something about this particular scene that refuses to be flattened out. But also, in the lower left corner—something else that I know I’ve never noticed before. It appears to be a hand. Is it? It looks like a hand extending into the scene from just outside the frame, like it’s reaching for my sleeping grandfather. It may or may not be a hand.

It could be a distortion, something else entirely, but in considering it, something’s been opened, and I can’t un-see it.

“What does it mean to confront the nothingness, to touch its fullness? This is a question that cannot be answered in the abstract, not once and for all, but must be asked over and over again with one’s body.” (Barad, “Troubling Time/s”). I find myself physically extending my own hand towards the screen right now, in front of this photo, foolishly trying to replicate the pose, testing it out to see if it could be a hand. It looks entirely plausible; in fact, my own hand looks remarkably like the one that I think I see. It took me 53 years to notice it. Barad writes that “touching oneself involves touching Others. The renormalized self is a collectivity, not an individual, in an undoing not only of self/other but human/nonhuman.”

This is how I’m starting this work, in a very literal sense: loosening my own queer timeline, before I turn towards others, trying to open it up where I can, stretching, reaching, touching, re-turning. I need new strategies, new methodologies, for entanglement. Oh look, there I am.

I. LOVE. THIS. POST. *no shocker there