An ethics of entanglement

The very first gay publication is missing

“An ethics of entanglement entails possibilities and obligations for reworking the material effects of the past and the future. As the quantum eraser experiment shows, it is not the case that the past (a past that is given) can be changed (contrary to what some physicists have said), or that the effects of past actions can be fully mended, but rather that the ‘past’ is always already open to change. There can never be complete redemption, but spacetimematter can be productively reconfigured, as im/possibilities are reworked. Reconfigurings don’t erase marks on bodies—the sedimenting material effects of these very reconfigurings—memories/re-member-ings—are written into the flesh of the world. Our debt to those who are already dead and those not yet born cannot be disentangled from who we are. What if we were to recognise that differentiating is a material act that is not about radical separation, but on the contrary, about making connections and commitments?”

—Karen Barad, “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come,” final paragraph

I’m already feeling the pain of the archive. I’m realizing that I always have been. Barad offers a way to navigate through it, I think.

Peering, unveiling

I’ve been doing research into Henry Gerber, born in Germany in 1892. I wasn’t familiar with him until recently, when I applied for an artist’s residency with the Institute for Public Architecture on Governors Island. To prepare my application, I googled “Governors Island” and “gay history,” and this National Park Service webpage, “LGBT History on Governors Island,” came up as one of the only results. Gerber is recognized as an early gay-rights activist, having founded the very first gay organization in the US in 1924: the Society for Human Rights. After being arrested for publishing and distributing the Society’s newsletter (the first of its kind), and losing his job with the US Postal Service, he enlisted in the US Army and was stationed on Governors Island from 1925 until 1942.

Also on that NPS page:

“Peering into the little known corners of Governors Island history can unveil surprising things …

… Gerber was subject to beatings, blackmail, and other forms of harassment because of his homosexuality. In February 1942, Gerber’s quarters, on Governors Island, were searched by G-2, the Army’s investigative unit, which found no evidence of illegal behavior. Although nothing was found, he was held in Castle Williams, the guardhouse, for weeks after the search.”

Here is an account of gay violence—“beatings, blackmail, and other forms of harassment”—at the very place where I’ll soon be living. The pain is already located there, even before I arrive.

So now it’s part of my story, too.

This webpage is the only “official” queer history of Governor’s Island that I can find—written by the National Park Service in 2015.1 Their account reinforces the ongoing marginalization of queer history, using the language of shame and invisibility to introduce Gerber’s narrative as residing in the little known corners of history that we can peer into to find surprising things, which must be unveiled if they are to be known. The language is Othering, presenting queer history as a recently discovered novelty, entertaining even, to a mainstream audience.

In contrast, a detailed history of the US military’s longtime presence and activities on Governors Island—the perpetrator of the violence upon Gerber’s life and others—is readily found, having been deeply researched, documented, and presented repeatedly (and positively) as the known, visible, proud history of Governors Island.

What if Governors Island was always already queer?

I just found out that I was accepted to the IPA residency, so now I’m getting ready to live and work with this material on Governors Island for 11 weeks this fall. In August, I’ll visit the ONE Archives at USC in Los Angeles, which has a very small collection of Henry Gerber papers, to see what else I can find.

Double erasure

After establishing the Society for Human Rights in Chicago in 1924, Gerber published two issues of the Society’s newsletter, Friendship and Freedom. It’s the very first gay publication in US history, yet no copies are known to exist. We only have a single photograph, which shows the cover of the first issue. It’s both there and not there.

The photo was originally published in a Magnus Hirschfeld article about homosexuality in Germany in 1927 (in this book), and then reproduced in 1978 in the book Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A., a massive account of queer history by Jonathan Katz (pictured above). After the second issue of Friendship and Freedom was mailed to members, the wife of one of the organizers went to the police to report them, and Gerber and two others were arrested, briefly jailed, and put on trial. The judge ruled that Friendship and Freedom was lewd and obscene and illegal to mail (because of the Comstock Act of 1873). Gerber paid a hefty fine, and lost his job with the postal service.

“Our debt to those who are already dead and those not yet born cannot be disentangled from who we are.” (Barad)

One of the other men arrested and jailed was the Rev. John T. Graves, a Black pastor in Chicago who was the first and only president of the Society for Human Rights. As the leader of the very first gay organization in US history, 45 years before Stonewall, we should know more about Graves, but sadly there is nothing. His name is only ever found as an attachment to Gerber’s scant story. He’s a footnote to a footnote, an even deeper erasure, lost within an already blurry and frustrating “little known corner” of queer history. Erasure upon/within erasure. Graves’s signature and address appear on the charter for the legal incorporation of their non-profit, and he’s briefly mentioned in one of Gerber’s accounts of the Society, but Graves—a Black man who played a key role in queer history—remains practically unknown today.

Our debt—what is owed to Gerber, but even more so to Graves—is considerable. As queer ancestors who struggled for liberation but were unable to leave us much, I feel myself becoming deeply entangled with the im/possibilities of their stories. As little as there is. I’m searching for ways to make connections and commitments.

“… the ‘past’ is always already open to change.” (Barad)

I’m now searching for anything at all that might be related to Rev. John T. Graves, and I did find one thing. Here it is:

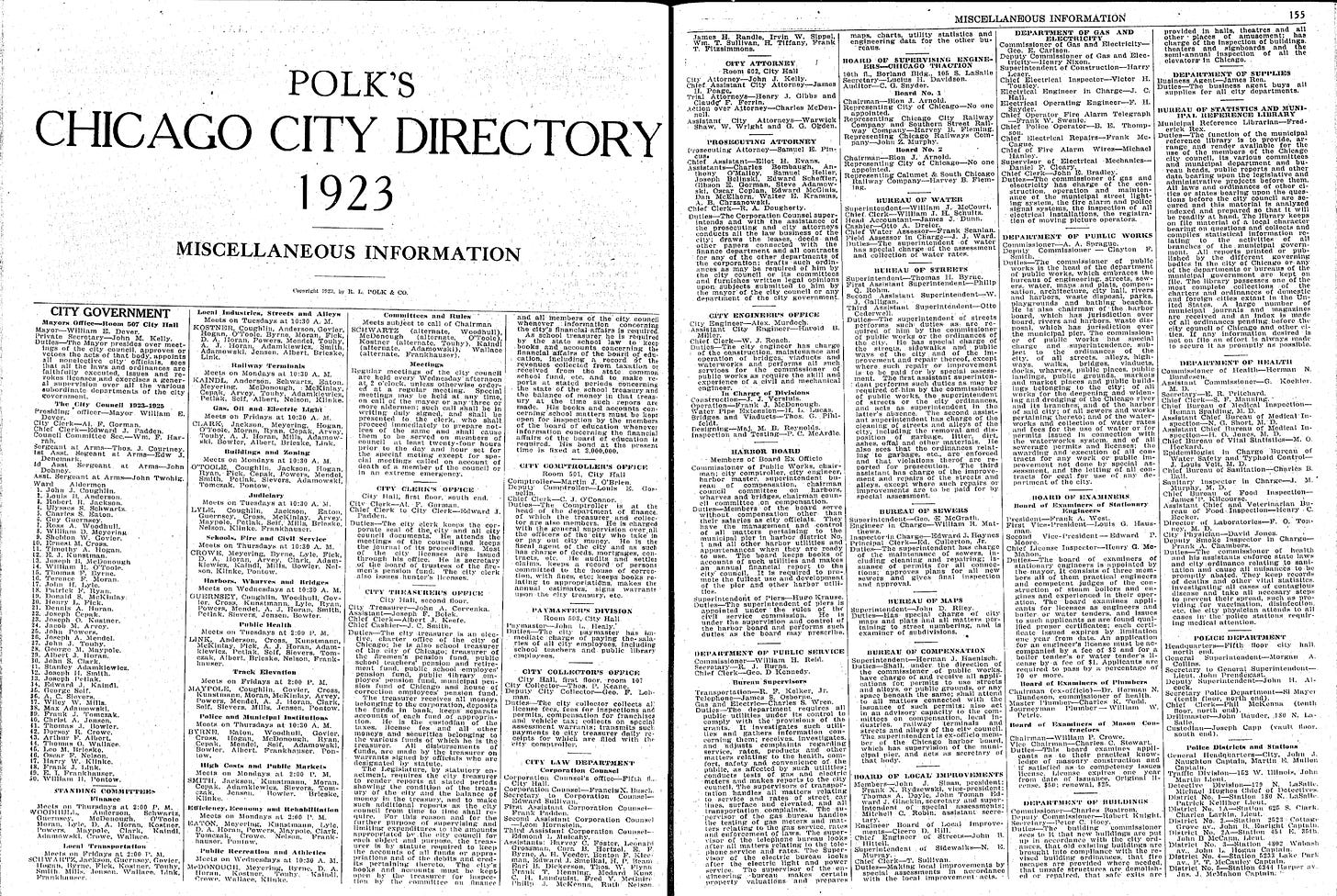

It’s a PDF of a 1923 Chicago city directory, and in the church listings, there is a “Rev. John T. Graves, pastor” listed under St. John’s Evangelist Church, at 4857 S. Dearborn. The time and the place line up, so it’s possible that this might be where Graves preached. I’ll continue to search for details about his life. If that church still exists, it’s no longer at that address.

So much is missing, so much owed.

The very first gay publication is missing.

The brief history of the Society for Human Rights, cut short when its organizers were arrested in 1925, is barely there.

Whatever the G-2 unit was looking for in Gerber’s residence on Governors Island: “nothing was found.”

Rev. John T. Graves is missing, as is his own place in queer history.

What was the relationship between Gerber and Graves? I’ll visit the ONE Archives looking for some clues, in Gerber’s voice, in his correspondence, in his papers (“0.2 linear feet. 1 archive carton”). Graves, so far, has no voice in this story.

A webpage,

a charter,

a photograph of a newsletter,

a city directory.

Spacetimematter can be productively refigured, as im/possibilities are reworked. These scraps are painfully frustrating, but they are something, present with us now, and part of a past that’s always already open to change. There might be more waiting for us. These scraps might give us ways to occupy and shape our story as a continuous flow through a troubling spacetimematter, rather than as differences and separations. They might give us ways to rework and refigure some of that pain that’s always already waiting for us.

I did find another, less official, but far more interesting account of Henry Gerber on Governors Island. Jeremy Sorese did a residency with the Shandaken Project in 2020, and produced this beautiful self-published publication (PDF) of Gerber’s story, incorporating his own questions about time, place, narrative, and identity.