I’m looking for places where time can be accessed differently. Landscapes and sites where it’s possible to embody multiple times and spaces at once.

On Tuesday, August 27, 2024, I left my house and rode my bicycle to the end of Congress Avenue, in Providence, RI. I crossed Elmwood Avenue at the Walgreens, rode through Reservoir Triangle past the spot where a statue of Christopher Columbus stood for 120 years (it was removed and relocated in 2020 but the base remains), and continued onto Reservoir Avenue as it rises up and crosses over the final stretch of the northbound Amtrak Northeast Corridor line before it arrives at Providence Station.

In-between the train tracks and a Popeye’s Chicken is a turn-off into the entrance of a new Tesla service and distribution center. It opened earlier this year. I cross the Tesla parking lot, enter the adjacent parking lot of Dr. Jorge Alvarez High School, and ride over to a small opening in the chainlink fence that serves as the entrance to Mashapaug Park. Right before me is a view of Mashapaug Pond, the largest freshwater pond in Providence. A path stretches to my left and to my right. Another path leads down the hill to the pond. From my house, it took about 7 minutes to get here.

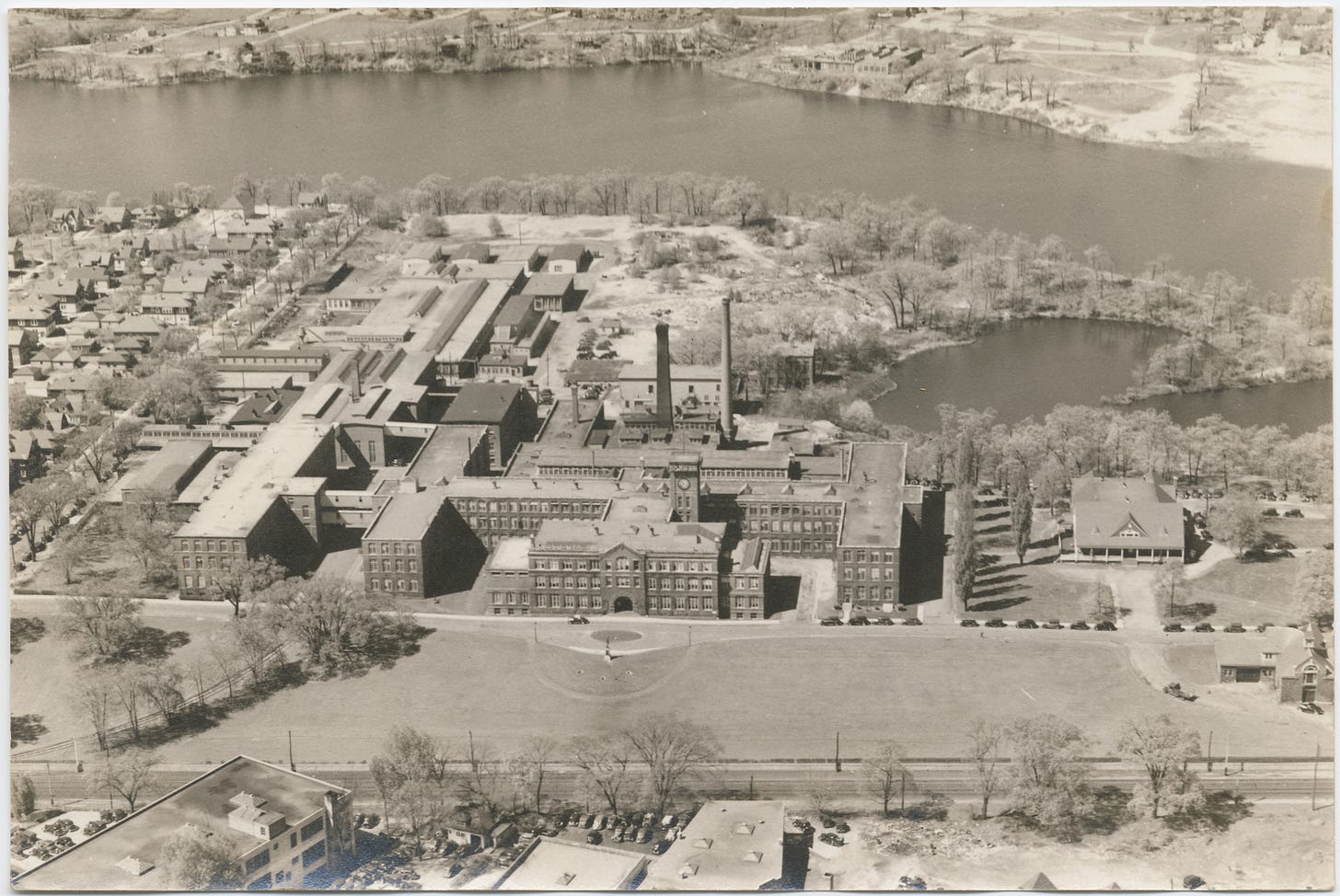

This place—the pond, the park, the Tesla center, and the high school—is the former site of the Gorham Manufacturing Company, at one time the largest maker of silverware in the world. It operated here from 1890 until 1986, and employed up to 1,000 workers. It manufactured countless household items, precious objects, artworks, and the statue of Columbus that was removed just a few hundred feet away. The firm was bought by Textron in 1967, before it was dissolved in 1986. Now, there’s no visible trace of Gorham. The 30 factory buildings that once stood on the site are gone.

I look at my phone, and read today’s headlines. Kamala Harris says she would appoint a Republican to cabinet if elected president. Wisconsin and Illinois health officials report three deaths from West Nile virus. Special relationship at risk if UK bans arms sales to Israel, says Trump adviser. Weather Now: Much Cooler and Less Humid Today. 4 swimmers rescued from rip current at East Beach.

From where I’m standing the landscape around me looks undisturbed, but it’s been totally engineered into its present condition. Gorham poisoned the surrounding area with industrial toxins throughout its history. Everything that I can see—landscaped earth, trees, fields, pathways, vegetation—has been grown and constructed during the last 20 years as part of an enormous remediation process (documented by the RI Department of Environmental Management here). Despite clean-up efforts, pollutants still persist in this place, in the outdoor air, the soil, inside the High School, and in the pond. The contaminants are from chemicals used by Gorham to clean metal and machine parts. They seeped into the land and entered the groundwater. These are human carcinogens that remain in the ground and eventually evaporate as dangerous gasses when exposed to air.

West Elmwood

Gorham’s contamination is just part of the violence of this place. For decades, the neighborhood of West Elmwood stood across the pond from Gorham, bounded by the railroad tracks, the Cranston city line, and the shoreline. This had been a significant Narragansett settlement for centuries, eventually transforming into one of the first neighborhoods in Providence where people of color owned homes. In 1962 the City of Providence totally destroyed West Elmwood, displacing 567 families, almost all people of color, in the name of urban renewal. “The Providence Redevelopment Agency bulldozed West Elmwood to construct the Huntington Expressway Industrial Park. Studies describing unhealthy and unsafe living conditions in this portion of West Elmwood were used to justify the city’s action.” The loss of history, homeownership, family relationships, kinship, and neighborhood culture was profound.

Today, the 117-acre industrial park includes tenants like Amazon, Brown University, Lowe’s, Providence Water, Restaurant City, Prime Storage, and PBS. The literal bulldozing of West Elmwood, resulting in a tremendous increase in impervious ground cover throughout this area (asphalt, concrete), now causes rainwater to mix with road salt, fertilizer, car fluids, and other pollutants, flowing directly into the Pawtuxet River Watershed. The contaminated runoff enters three interconnected ponds that border the industrial park, flowing from Tongue Pond to Spectacle Pond to Mashapaug Pond. From there, the water feeds directly into nearby Roger Williams Park, and eventually drains into Narragansett Bay, which leads to the Atlantic Ocean. Excess algae growth, lead, and compounds like dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are present, making it unsafe to eat the fish, to swim, or to come into contact with the water or soil.

These are some of the basic facts of Mashapaug Pond and the surrounding area, easily found online. It’s a recent story, given the long trajectory of this place, from its geological formation, to the Narragansett, Wampanoag, and other tribal inhabitants who originally defined this area, to the settlers who occupied the land, to now. How do we read a site? This basic information about the colonial transformation, the violent displacement and dispossession, and the industrial contamination and subsequent re-engineering of this place is illegible by sight alone. Other legibilities are present here, and they require different kinds of work.

Another question might be: how can we feel a place? Sensing, research, listening, reflection, patience, repetition.

I’ve been visiting this place again and again and again, trying to feel it, make sense of its material, and sense other legibilities. I’m taking an embodied inventory, a material accounting of the agents who (will) co-exist(ed) here. These characters aren’t the only players in the ongoing story of this place but they are the ones revealed to me lately. Every time I look, I find more. Each of these characters is simultaneously a ruin and a monument, rising and falling. Each one is both present and not present, visible and not.

This site, like all sites, brings multiple agents—monuments, ruins, timelines, spaces, relations, characters—together into a place. All at once, this place is formed by a remarkable publication about West Elmwood by Lucy Asako Boltz; the human and non-human workers at Amazon Delivery Center DRI1; the asphalt; the Amtrak and MBTA commuters who travel through this place each day; the Tesla workers and vehicles; the students and staff of Alvarez High School; this 304-page status report by EA Engineering summarizing the most recent monitoring of toxic contaminants at the High School; and the rabbits and hawks and insects and algae and cats who make Mashapaug Park their home.

Tactical Grey

One of these agents is the back of the new Tesla service center, covered in “Tactical Grey” paint, facing Mashapaug Park. Tactical Grey is the standard interior color of the Tesla Cybertruck. Visually, Tactical Grey is a mid-range average color, but it’s not neutral. Facing the pond, it’s a sharp reminder; it recalls the history of silver and other metals that were processed at this site for much of the 20th century, as well as the color of lithium—the alkali metal that’s extracted today in the US, Argentina, Chile, Australia, Canada, and Bolivia, for Tesla’s electric vehicle batteries.

Present or not, seen or not, these agents form multiple realities. This site is a survival network of entangled agents—beings and relationships, living and non-living, toxic and non-toxic—that persist across time and space through their specific intra-actions. Ancestors, agents, players, and possibilities.

Who and what gets to persist?

Plume

The Plume continues to spread, urgently, quietly, invisibly, under the parking lot between Tesla and the High School.

Dr. Jorge Alvarez High School opened in 2006, before remediation efforts were complete. It sits within the former footprint of the Gorham buildings, on contaminated soil, as does the Tesla service center. The High School mainly serves immigrant families from Cambodia, Ghana, Vietnam, and the Dominican Republic in the Reservoir Triangle area, with a diverse first-gen student population that’s 90% bilingual.

Underneath the asphalt of the shared parking lot is a large contaminated groundwater Plume. The Plume is a billowing area of poison material in slow, continuous movement, its energy flowing below the surface. It reaches, stretches, blooms. It spreads and shows, out of sight. Despite many years of remediation, elevated traces of toxic materials like trichloroethylene (TCE) and tetrachloroethene (PERC) continue to be detected in the air inside the High School, most recently in the Library, the Kitchen, and in Classroom 116. This is a seeping, a spreading, a gassing, toxic, alive and flowing.

5:43PM: a MBTA commuter train speeds by.

This place, all of it—this parking lot, the buildings, the Pawtuxet watershed, the beings who live and work here—is a ruin in reverse, a collection of timelines that can be played backward or forward into what passes for a future, like a tape in a player.1 The ruin reveals itself relationally. The ruin reveals itself in all directions, rising and falling. Playing back to a time before the High School, before the Plume, before West Elmwood, before Gorham, before Columbus. Before monuments. West Elmwood appears to be gone but that’s only one (visible) reality; another is that the trauma and violence of the elimination of West Elmwood persists in the continuous, endless flow of poison that pulses through the city’s waterways, as well as the inherited pain and dispossession that continues to impact all of its ancestors.

Gorham appears to be gone but that’s only one (visible) reality; another is that Gorham is here, and will always be here, a never-ending monument and ruin, deep within the transformed site and in this movement and energy of the Plume, the effects of the Plume and Tactical Grey, these other characters that continue to spread and poison.

Altogether, this place—with its earth and water and this cast of characters—rises and falls into ruin, towards an enormous spectrum of histories and futures. Going beyond what passes for a future on the surface of right now, beyond the surface of the visible. This inventory of a ruin in reverse, rising into ruin, beyond what passes for a future, forms a loose sketch for an embodied experience, one that I try to access again and again and again. It’s a need, a desire, a possibility. As a ruin in reverse, as an embodied experience, here at this place, one might sense these other timelines in all of these intra-actions: after the Plume exhausts and expends itself, after the High School is closed and demolished, after the pond is drained and transformed into something else.

Slag Pile

The Slag Pile sat (sits) on the shore of Mashapaug Pond until it was removed in July 2006. It can’t be defined in legible, precise terms; it’s an approximation in time and space. Even its presence—whether or not it had been totally, properly removed—was contested in a letter from “Concerned Citizens of the Reservoir Triangle and South Providence” to Textron on November 14, 2006. The Concerned Citizens identified Gorham Building V as the site of Secondary Copper Smelting, discharged directly into Mashapaug Cove through two 6-inch waste lines. The enormity of the Slag Pile cannot be overestimated; it held (holds) everything that cannot be contained in the intricacies of these beautiful products produced by Gorham, including lead, dioxins, and furans. There should be no surprise that the by-product of these precious artifacts that are purchased, collected, circulated, auctioned, and stored, is this: excessive spreading haunting toxicity. It should come as no surprise that the by-products of capitalism always include an excess of trauma, ever-lasting burdens, and impossible debt.

Dodder

Large areas of knotweed grow around Mashapaug Park, all along the train tracks behind the Amazon Delivery Center, in the area that was once West Elmwood. In some places the knotweed is a host to patches of Cuscuta (Dodder), a parasitic plant that doesn’t produce chlorophyll. After germinating, it looks for healthy plants nearby by sensing light reflectivity on green leaves. It grows towards the host plant, attaches itself, wraps its tendrils around it, and feeds on the host’s nutrients. Other names for dodder are strangle tare, strangleweed, scaldweed, beggarweed, lady’s laces, fireweed, wizard’s net, devil’s guts, devil’s hair, devil’s ringlet, goldthread, hailweed, hairweed, hellbine, love vine, pull-down, angel hair, and witch’s hair.

There are tents and other makeshift dwellings nestled here within the vegetation along the tracks, and I’ve noticed the tents in other places around Mashapaug Pond as well. People are using this space differently, independently sharing the site with other beings living and working here now, and other beings who will work and live here in the future. Many of the Amazon associates who show up each day at Amazon in Huntington Expressway Industrial Park are immigrants who are employed by Wutabon, Inc., a “delivery service partner” contracted to Amazon, purporting to “reimagine social services.” There are different kinds of survival here, different legibilities of support, of recognition, of being.

Towards a queer embodiment of place

We need to better embody multiple, simultaneous times and spaces in order to know how to persist, and how to care for each other, while much of our queer history and much of contemporary life in capitalism works to take away the possibility of survival. Time can be queer here, at the rising ruins and its inventory of debts.

I share this embodied experience of broken, queer timelines with others who want to reach across time and space, searching for multiple truths; this is the possibility of survival. By each other I mean: others living and others already dead, and others not yet alive. I’m searching for places where time can be loosened because my own timeline, the one I inherited, is broken. When I feel myself falling outside of linear time, I try to embody queerness as it was, as it is now, as it will be; all possible ways of being. This is a queer feeling, a queer sensing, of always reaching—for something that’s not quite ready, not fully visible, not fully present. I’m looking for places where I can sense other timelines, where I can dig deeply, where I can more fully reach for these monuments and ruins that form places. I want to understand the less apparent, entangled relations that make a place like Mashapaug Pond, which is my home. I want to access the never-ending transformation of a place like Mashapaug Pond through these survival networks of entangled agents and relations.

Once accessed, I want to animate these characters by letting them act on my body, and in my heart. They might be players in an opera or a play or a dance. They might be present and potent and visible like that. There might be a way to collapse different time scales together into one place, like the scale of Tactical Grey, the scale of Dodder, the scale of the Plume, the scale of the Pawtuxet Watershed, and the scale of the violent histories of Columbus and the City of Providence and Brown University that surround us and are embedded in this place. All of these monuments and ruins that travel back and forth, rising and falling, ever-lasting, persistent: they’re here. These are multiple truths, all possible histories and futures, here in this place that we (will) call(ed) home.

The idea of a ruin in reverse is borrowed from Robert Smithson, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey” (1967). He writes about the emerging infrastructure of an industrial landscape, and the different kinds of realities he experienced while exploring this place, and his approach directly informed my thinking about Mashapaug Pond. I was also greatly inspired by this response to Smithson’s essay by Ellen Mara De Wachter, Suburban Odyssey: Revisiting Robert Smithson’s Passaic (2018), a video essay that looks for other kinds of realities and politics in Passaic, fifty years later, monuments of failure and neglect that point towards lived, human experience in the current moment.

This was lovely. Thank you! I think you might like this https://naive-yearly.are.na/benjamin-earl

This made me have so many tangential thoughts and feelings. I also wanted to mention a book that I haven't read, but have heard a lot about via my gf who read it over the course of a year, that feels adjacent to some of the themes I felt in this writing. It may or may not resonate. Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn. Thank you as always.