Proximity artifacts

What is an intimate typography? Tracing, rubbing, touching, and the search for connection in distant forms

Saturated with memory for me

Sometimes I do time travel workshops. I was invited to do one titled “Archives offer the possibility of survival” at the University of Texas in Austin in March 2025.1 Organized in two parts, it started with “IN THE ARCHIVE—a prompt for an encounter,” which focused on queer artifacts found in the collections of the Briscoe Center for American History. 24 people participated in the session—students, faculty, community members—choosing and documenting LGBTQIA+ items from collections of materials that I had requested in advance. Then we left the archive, to create new things: “AWAY FROM THE ARCHIVE—a prompt for the future.” We printed the images of our selections on brightly colored sheets of paper using a risograph printer, and used them to make annotated collages. The workshop concluded with a collectively-curated display of everyone’s creations on the wall.

I was so moved in that moment, seeing everyone’s capacity to directly engage with archival materials, sifting through and touching this ephemeral evidence, queer materials in queer hands. Publications, stickers, fliers, buttons, documents, photographs, scrapbooks, and then quickly, collectively, we generated an entirely new collection. I encouraged the participants to keep it as personal as possible, and to choose and document and make their work based on a logics of intimacy and felt experience while handling the items. I was hoping for an outcome where these queer artifacts might gain a new kind of life, emerging out of a collectively experienced design process that could be felt and shared with others in the room, and beyond.

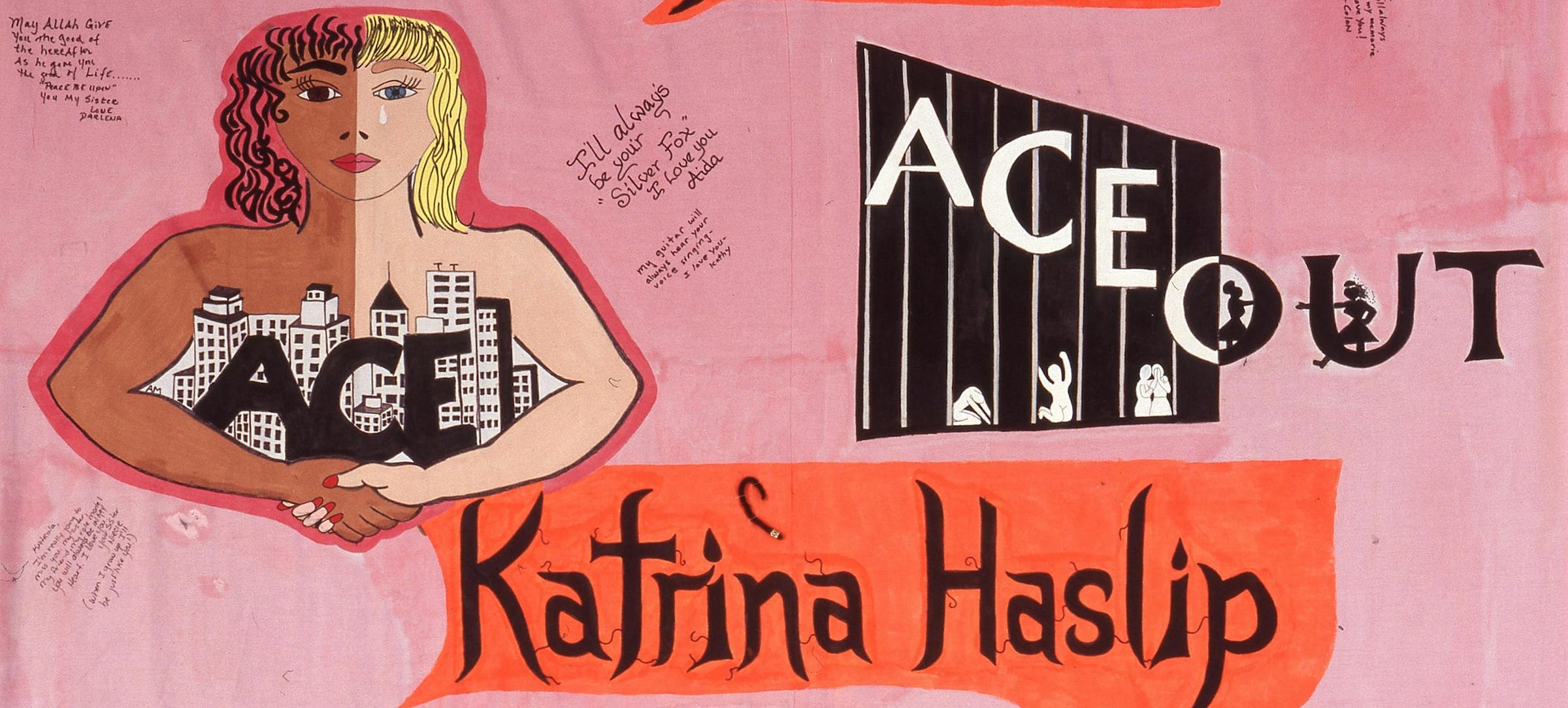

To my surprise, the scholar Ann Cvetkovich attended the workshop. Cvetkovich, who is Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at UT Austin, selected four items from the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) Austin collection, documents from the late 1980s and early 1990s, and assembled them onto a single sheet with handwritten annotations. On her collage, she noted: These documents are saturated with memory for me, and signed her name. I’ve been thinking about it ever since, how personal her reflective note was, of course, but also how it seemed to stretch those artifacts across queer time and space, so that they might reach us there in that room, and here right now. She unlocked something encoded there within those ACT UP documents, an emotional code, by selecting them and meaningfully pairing them with her own deeply felt recollection; in that moment, Cvetkovich was also part of the archive. She gave us evidence; Cvetkovich’s assemblage was an intimate act of history making, written in feeling, to be opened up and shared through lived experience. Those ACT UP documents, saturated and overflowing into the room, were able to touch us, to locate all of us on a queer timeline that included Cvetkovich, ACT UP Austin, and everyone in the workshop.

Afterwards, I returned to her landmark book, An Archive of Feelings (2003), to recall how she describes this process of moving through “sites of investigation” to discover the vibrancy of queer culture. The book is organized—

as an ‘archive of feelings,’ an exploration of cultural texts as repositories of feelings and emotions, which are encoded not only in the content of the texts themselves but in the practices that surround their production and reception.2

In noting that those ACT UP documents were “saturated with memory for me,” Cvetkovich brings emotional and personal matters into (and out of) the queer archive, getting closer to new cultures and “alternative modes of knowledge” within a learning context—students, colleagues, and other queer kin in the room at that moment who might be able to exchange something immediate and profound, while sharing their own work.

Forged around sexuality and intimacy, and hence forms of privacy and invisibility that are both chosen and enforced, gay and lesbian cultures often leave ephemeral and unusual traces. In the absence of institutionalized documentation or in opposition to official histories, memory becomes a valuable historical resource, and ephemeral and personal collections of objects stand alongside the documents of the dominant culture in order to offer alternative modes of knowledge.3

As my research continues I find myself giving more and more attention to affect and embodiment while working in the archive, allowing personal experience to contaminate the writing. I’m drawn to these moments where my own queer body moves in and around the artifacts I study. This is my design re-education, an un-learning that uses the material conditions of language—the social and political realities of its production and distribution—as the basis for understanding typography and design. Rather than a destination, the archive has become more of a backdrop for this work, as I try to understand, move, and navigate through the evidence of queer life, searching for the public and private acts of language that shape a body, a psyche, its memories. More and more, that body and those memories are my own.

Can the personal archive be the basis for a design education? Do our own bodies have the capacity to unlock earlier acts of language, and if so, where do they take us? Domestic archives contain the residue of life, in the domestic scraps, the ephemera, in the photos that survive, that we carry and take with us—of course this evidence holds value. And I propose that it’s not just the physical artifacts, but internal images too, even immaterial ones, that deserve our attention. There are queer typographies there in our histories, letterforms and graphic shapes and symbols that spell out other languages, remembered and imagined, different intimacies. We carry them with us, internally, in our homes, our hard drives, our bodies. What is an intimate typography?

Emil J. Klumpp

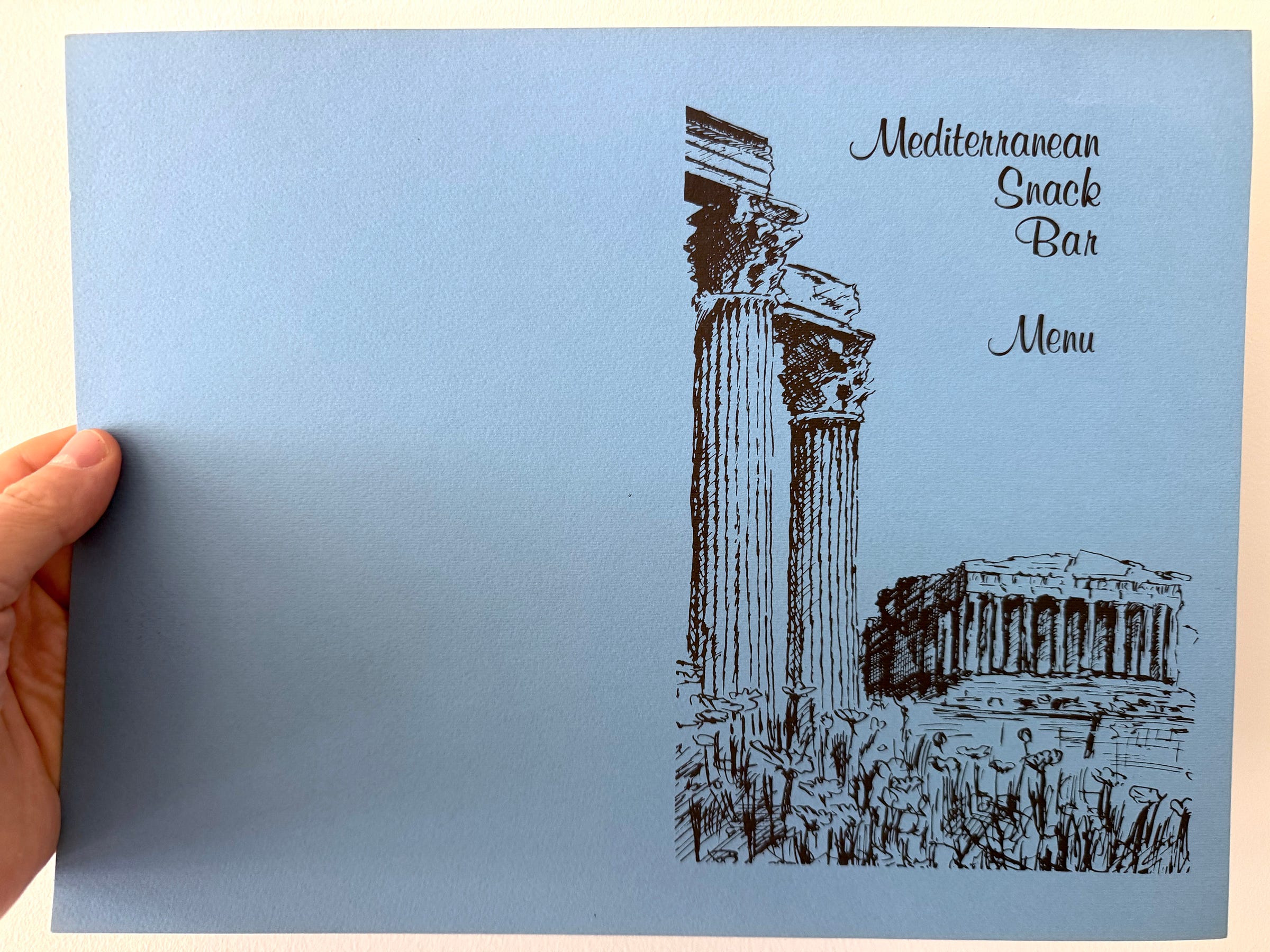

There was a whole graphic program there in the restaurant my parents opened when I was seven years old, neon letters in the window, the orange number “360” on the door, the hand-painted menu. It’s mostly gone now, the space renovated again and again through the years before closing in 2017, but a few photographs remain, holding a kind of power over me, images with a capacity to stir that seems to grow with time. They conjure something enormous in me, a whole world that still dwells there; I get access with these photos. Steve and Terri opened the Mediterranean Snack Bar on January 11, 1975, and I don’t remember much from that moment, except that I was sent away to stay with a family friend for a few days while my parents worked to get it open, serving souvlaki and gyro and falafel and spanakopita in Huntington Village, about an hour from New York City. They did this for 42 years.

How could this place, not just an abstract sense of it, but a specific space and moment in time, hold some kind of queer knowledge? How might I access and share in 2025? Honestly, I’m not sure. I’m trying to see this photograph as though I just found it in an archive, as though it isn’t mine, as if I wasn’t there. My parents don’t remember anything about the large light box mounted at the back of the dining room; it exists nowhere except in this photo. The hand-painted menu looks like it belongs in a pizzeria or an old-fashioned ice cream parlor, and I wish they could tell me more, like who did it, if it was a professional sign painter, and how it came to be that the letterforms on their menu would be so exquisitely hand-painted and lit from behind. My father can’t recall. I’m scanning carefully, slowly scrubbing through all of the details in the photo, like I’m able to peer through a wormhole where I might see myself there at the checkered table cloth, the pull-down ladder that led upstairs to my father’s office just visible through the kitchen door. I was terrified of that ladder, always scared to climb up into his world, but it was even worse coming back down, because I had to sit on the edge of the opening and lower my legs into the kitchen, ashamed of my dangling body that I imagined falling down in front of the kitchen staff who worked for my father.

And that travel poster in-between the pay phone and the clock looks vaguely modernist, with lower-case sans serif letters spelling out “rhodes;” I know that the lack of an initial capital letter puzzled me as a child. I try looking for the poster now, a reverse Google Image search that yields nothing.

I ask my father to look for the original printed menus, and he texts a photo back to me from the basement; it’s black ink printed on blue paper. There’s an illustration of the Parthenon in the distance, a couple of Corinthian columns, and a field of poppies in the foreground. In Greek mythology, poppies were used as offerings to the dead. I haven’t seen this menu in decades, and it’s an instant trigger of feelings and sensations, like seeing myself in a dream, as if I’ve come across something familiar in one of the archives that I visit, except it’s from deep within my parents’ house, stored away when they retired. The menu barely survived, but it did, and that’s all that’s important. The emotional charge of this thing is substantial, saturated with memory for me, something to do with the part it played, a prop, something that was there, part of the mise-en-scène of my childhood, overflowing into this very moment.

Had I ever really seen it? These two columns on the cover of the menu couldn’t be part of the Acropolis, right? Corinthian came later. Some quick searching brings me to the Temple of Zeus in Athens, some distance away, and sure enough, it’s a perfect match. A kind of compressed space, some artistic liberties taken. I asked my father where the illustration came from; he doesn’t remember.

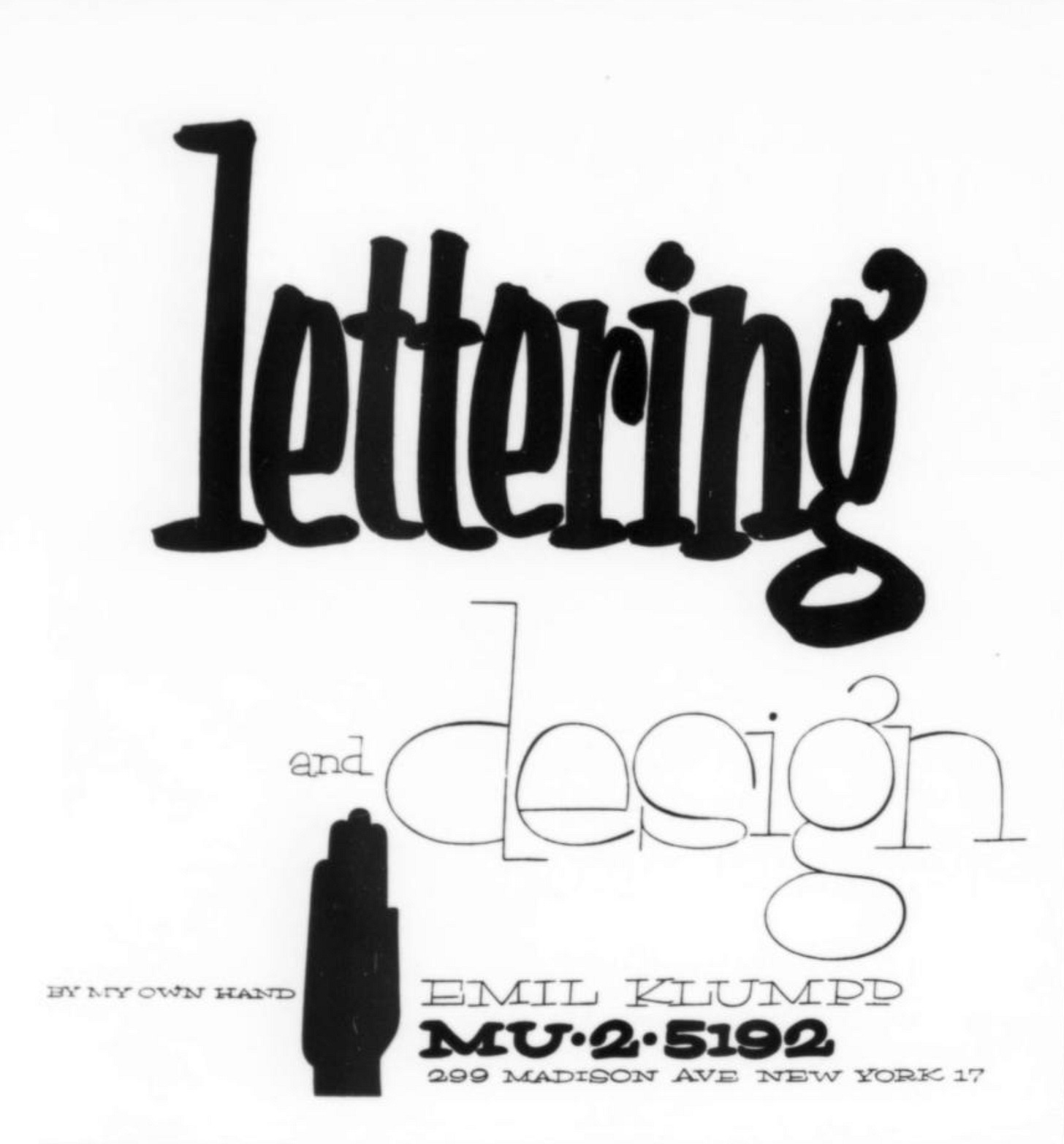

Floating above the ancient temple are the words “Mediterranean Snack Bar Menu” right justified in a bright, vertical typeface, a loose, unconnected script with a handwritten feel. I deduce that it’s Murray Hill Bold, designed by Emil J. Klumpp in 1956 for American Type Founders. I went searching for it at the Updike Collection on the History of Printing at the Providence Public Library, and found original marketing materials for Murray Hill promoting it as a “casual” face for advertising. It was described as a “modern and practical script design” but coded “feminine” with the sample language shown, including several advertisements addressed to “ladies.” There was nothing Greek about it at all; rather, it embodied a kind of post-war American optimism, with bouncy energy, lending itself to playful design treatments that might float the letterforms off a baseline, like on this 1958 album cover for the girls. The name Murray Hill was specific to New York City, from the telephone exchange “MU” for the Manhattan neighborhood that was home to many of the biggest advertising agencies at that time, as well as Klumpp’s studio. An ad for his hand lettering services notes his address as 299 Madison Avenue, phone number MU 2-5192.

One of those type specimens said Murray Hill would “inject a note of refreshing informality into what otherwise might be ‘just another print job;’” remarkably, “refreshing informality” is exactly how I would describe the early success of the Mediterranean Snack Bar. My father offered new food to our town; it wasn’t fast food, or a diner, or fine dining, or a pizzeria. He served what he knew: souvlaki, gyro, sausage, falafel, and Greek salad that many Long Islanders were eating for the first time. When the Snack Bar opened it had no chairs, because the Town of Huntington wouldn’t allow seating without dedicated parking, so my parents purchased high standing-only tables. A few months later, they appealed and were given permission to have seating, so they printed a menu for sit-down dining. Given Murray Hill’s popularity, I’m guessing that it was one of a few typefaces recommended to my father by the printer; it probably just felt right. This typeface played a tiny part in my parents’ success, but it’s got a firm grip on me now, something I can only encounter in this way, a door opening up into mid-century American type design from this childhood prop, an artifact that barely survived but one I will now treasure, this printed menu from 1975.

Isle of Sappho

My father emigrated from Lesvos, Greece on April 14, 1963, 12 years before the menu was printed. Docked for a few days in New York City, he decided to walk off the ship where he was employed as a junior engineer, and make his way east to the town of Huntington, on the north shore of Long Island, in search of other ways of living. Soon after, a cousin got him a job as a dishwasher at the Colonial Diner, a Greek place in town, and that’s where he met my mother, who was a student waiting on tables there alongside my grandmother and my aunt. My parents were married in 1965, my dad became a US citizen, and I was born three years later, just before the Stonewall riots.

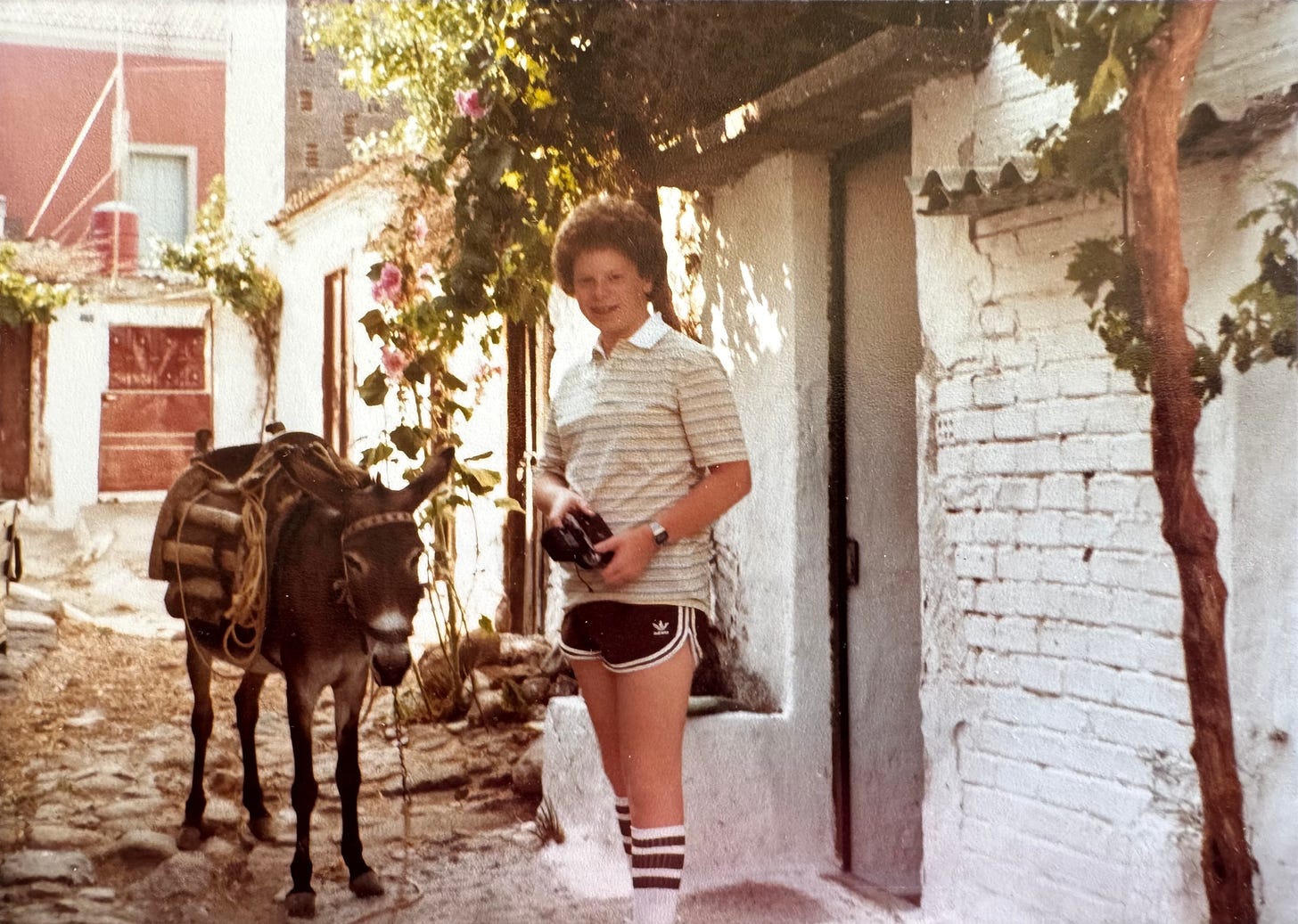

Throughout my childhood, we traveled to Lesvos to visit my grandparents in the house that they built at the center of the island, in the tiny village of Agia Paraskevi. At some point, probably as a young teenager, I figured out that Lesvos (sometimes spelled Lesbos) was the origin of the word lesbian, although I didn’t know why, and I instinctively knew not to discuss this with my father or anyone in the village. I’m pretty sure no one ever brought up the ancient poet Sappho during these trips, Sappho who was born on Lesvos in 630 BC, either in the town of Eressos or the main port of Mytilene, a queer ancestor who went on to name an entire culture with her island, a whole history, a complete identity, through the fragments of her homoerotic poetry that survived for thousands of years. I avoided telling anyone these origin stories before I came out at 18. Being gay was already a source of shame for me, even before I knew what it meant, before I understood anything about queer kin or Greek ancestry and how these identities would become so entangled for me later on. I didn’t yet speak any of the languages—Greek, queer history, gay desire—that would go on to shape my life.

What do we find in our own internal typographies? It’s an individual pursuit, a journey not easily shared, a kind of search we typically don’t encourage in design school. Instead, we rely on common, culturally-defined meanings and shared histories. That’s understandable, I know—we want students to become fluent in those cultures, those social, technological, and political forces that collectively shape our knowledge of art and design and how they came to be. But in this experiment, we approach typography differently, deeply, through the meanings we excavate in lived experience. Murray Hill isn’t Greek, and it isn’t particularly queer, but in extracting it from the basement and locating it deep within my own psyche, I can try to stitch something together. It’s just a stitch, this typeface, that language spelled out in 1975. The words “LARGE,” “SMALL,” “HERO,” and “TO GO” painted onto the menu board in their own slant so they could fit, and the way “Greek Pastry” has a different style; these are all tiny stitches. Here’s some meaningful language that played a part, a role, each letter, each word a character in my own formation.

Proximity artifacts

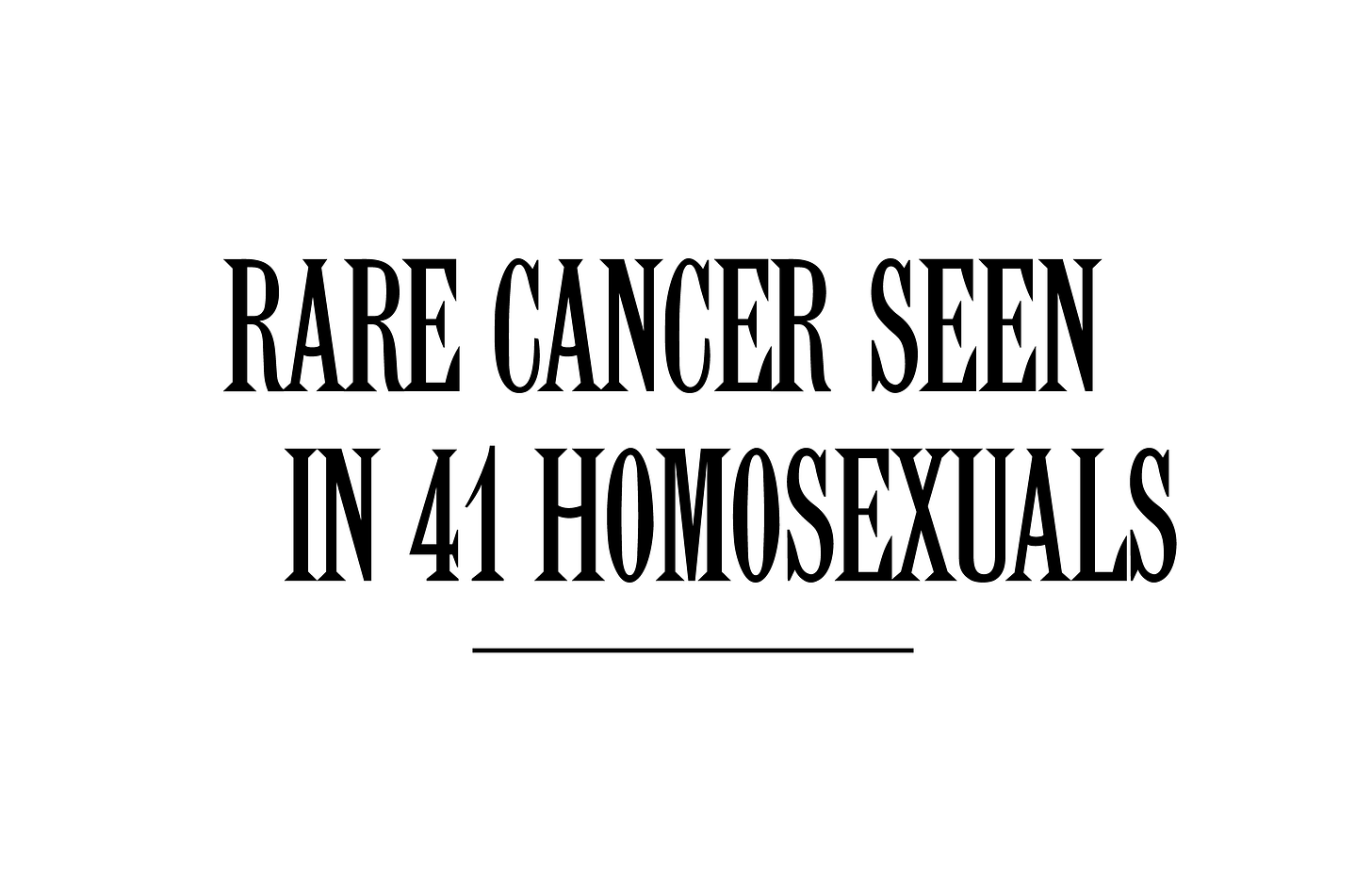

And then there’s another way to feed the internal archive, not just the artifacts we take with us but those we grab onto later, when we realize we were on a timeline we didn’t know existed. Filling in the gaps, I’m looking around for those designed artifacts that were there, around me, nearby, but unknown. I’m finding intimate typographies now in things that I never knew were missing, things that don’t come from my archive but still haunt it, somehow part of my memory but not held within it. Proximity artifacts from parallel timelines that jump over to haunt me, like this New York Times article that appeared in print six years after the Snack Bar opened, on July 3, 1981, Section A, Page 20, with the headline “RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS.”

What did I know about the headline? I never saw it as a 13-year-old, I’m sure of it. I probably first learned about the disease from Long Island’s Newsday, so I need to look through their archive. But the NYT article is a well-known media artifact from my adolescence, from the very early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis, now easily found online. It wasn’t until thousands of cases later in May 1983—10th grade—that the disease would appear on the front page of the Times, media negligence that mirrored the homophobia, racism, social neglect, and necropolitics fueling the crisis. That initial mention in the NYT was the most visible report in 1981, and laid the foundation for how the disease would come to be perceived, “that what came to be known as the HIV virus posed no threat to people other than cisgender homosexual men and some cisgender women. Black people were not mentioned, nor were intravenous drug users, people of color, and certainly not transgender and gender non-conforming people—all of whom were impacted by HIV then, as now.”4 Ted Kerr’s writing of that media history is crucial for understanding the crisis in a more intersectional, truthful way, how “underscoring much of the reporting at the time was the real and perceived homosexuality of the early patients. Unmentioned was a more nuanced understanding of sexuality or race.”5

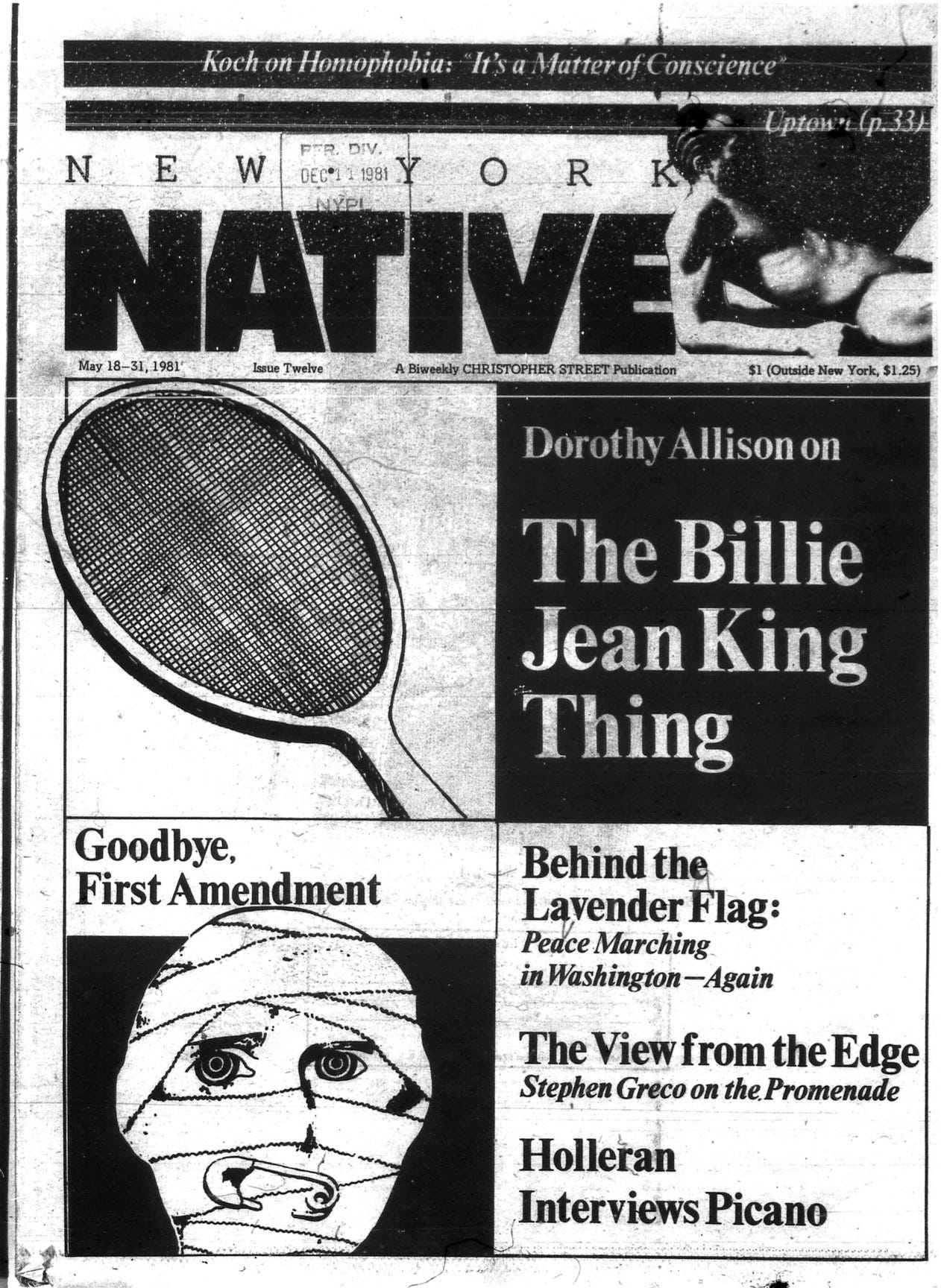

Weeks earlier, The New York Native published the headline “Disease Rumors Largely Unfounded” to accompany a short article by Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., the first public accounting of the disease. Mass wrote that “of the eleven cases this year that have been tentatively identified as community acquired, only five or six were gay.” Mass would go on to co-found the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). The Native article pre-dates the Centers for Disease Control’s “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” (MMWR) on June 5, 1981 by only two weeks; the CDC reported on five unusual cases of pneumonia in gay white men in Los Angeles, but neglected to mention additional patients who were Black, including one straight Black man from Haiti.

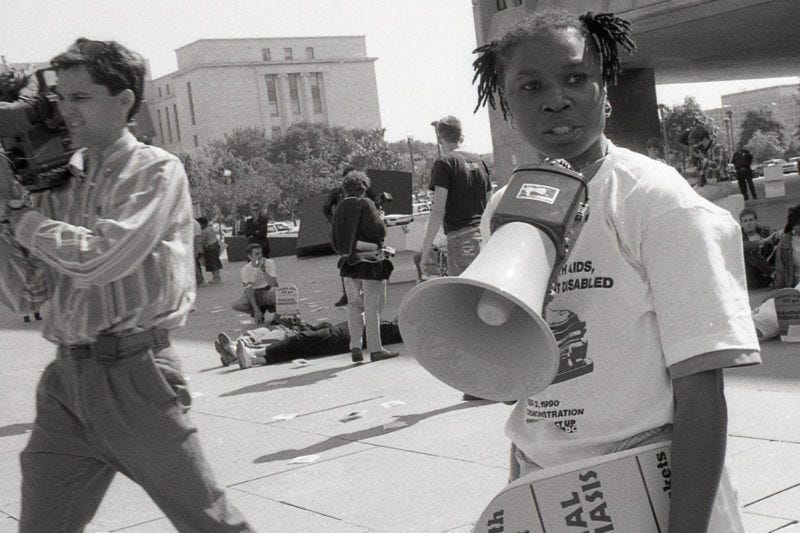

As I write this now on July 3, 2025 I see the NYT headline from the summer of 1981 in my Instagram feed again. It’s there every year as a collective reminder of how far into the future we’ve traveled, but also how erasure continues, perpetuating “the exclusion from the public imagination of communities of people who are not white, gay, cisgender men who are impacted by the virus now.”6 Missing are stories about educator and activist Katrina Haslip, “one of the most important and influential leaders of the movement of HIV-positive women fighting for their rights.”7 Haslip was diagnosed with HIV while incarcerated at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in New York in the 1980s, co-founded ACE (AIDS Counseling and Education program) while incarcerated, and later founded ACE-OUT, a program to support women with AIDS navigating housing, medical care, and life after incarceration. Haslip’s work helped expand the definition of AIDS to include “people whose HIV-related illnesses had not previously been acknowledged: women, people who inject drugs, poor people, people of color, and anyone existing at the intersections of these ways of being alive.”8 Haslip died from AIDS-related illness on December 2, 1992, but she was never officially registered as having died of AIDS because of the government’s limited definition of the disease. “I am, and have been, a woman with AIDS despite the CDC not wishing to count me. We have compelled them to,” she stated in a bedside interview at Roosevelt Hospital with a New York Times reporter.9 The expanded definition of AIDS, which she worked so hard to change, went into effect one month after her death.

We can rewrite our timelines to include Haslip’s power, activism, and fierce advocacy. I’m seeing the AIDS Memorial Quilt panel dedicated to Haslip right now for the first time, which includes expressive hand-sewn letterforms stretching and extending in space to form her name, and remarkably, what appears to be a braid of hair sewn directly into the quilt above the “n” in Katrina. The letterforms are perhaps adorned with hairs, or loose threads, I’m unsure, but the care that’s gone into constructing her memorial is deeply felt across time and space.

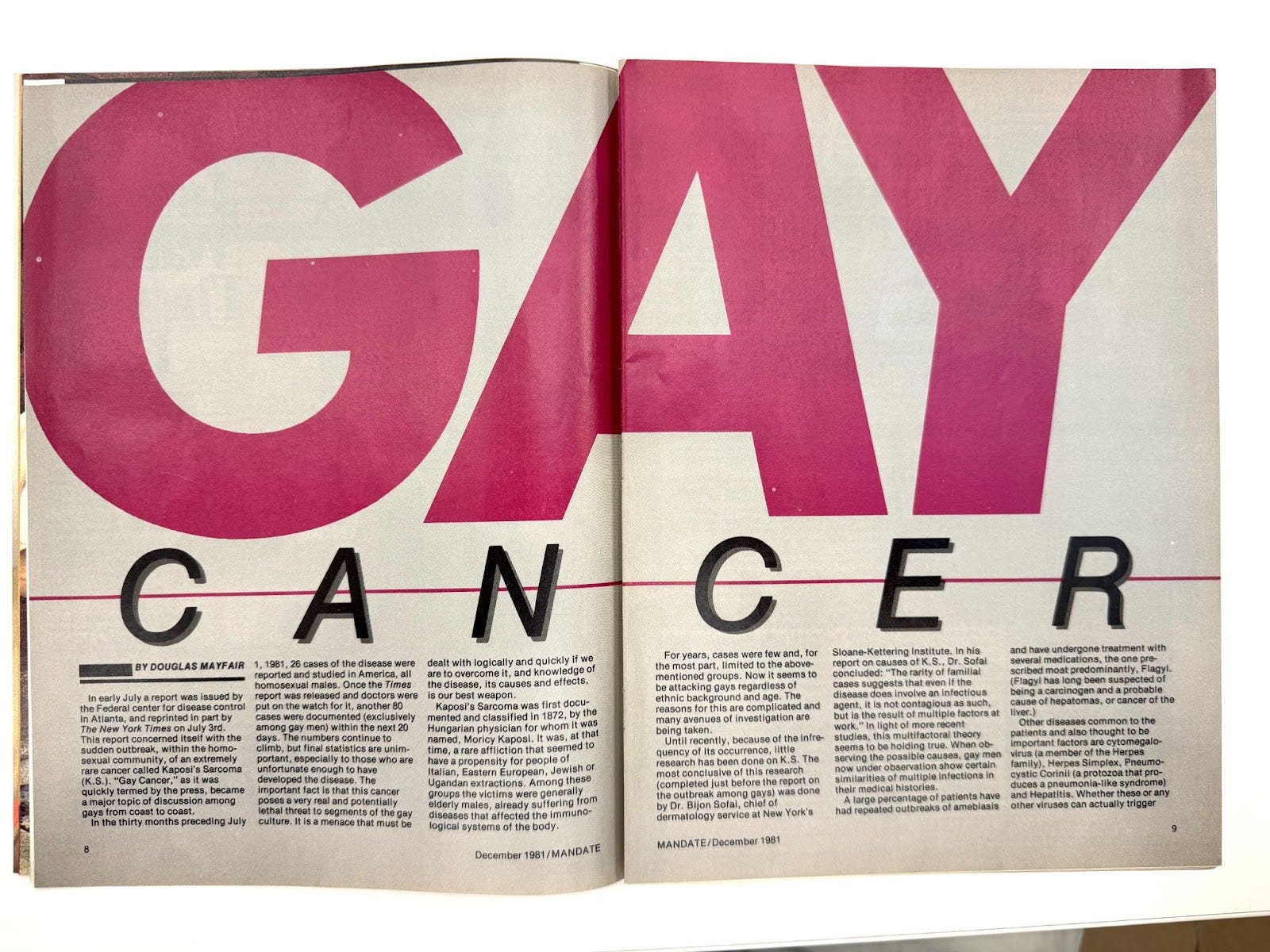

I’m looking through a box of random publications at the One Archives, and I come across the December 1981 issue of Mandate, a popular gay erotic magazine. I wasn’t focused on physique or porn magazines during my research, even though I knew there was incredible typography to be found on those covers. Dan Rhatigan has done some great work around this. But my stomach fell to the floor when I opened up that issue of Mandate and I saw the double-page spread that spelled out the words “GAY CANCER” in enormous letters. I couldn’t stop looking at those words at the archive in Los Angeles in October 2024, “GAY” set in Futura Bold Italic and “CANCER” set in Helvetica Light Italic, the “GAY” letters so huge that they’re barely contained on the pages, the gutter slicing right through the “A” and a bright pink horizon flatlining through the word “CANCER.” And of course I recalled the famous headlines from earlier that year, and put them all together on their own early HIV/AIDS timeline, only five months apart, for my 13-year-old clueless self. 1981 happened, and I was there, except I wasn’t. I was confused, struggling to understand my body, unconscious and far away, still five years from coming out. There I am, that summer, standing awkwardly in front of my grandparents’ house in a small village on the isle of Sappho. It may have been July or August. It may have been July 3, 1981.

These proximity artifacts look strangely familiar. I’ve lived with them my whole life, even though I’m seeing some of them now for the first time. I’m experiencing them simultaneously in 1981, in junior high school, later in college, and again in 1991 when I moved to New York City, panicky on W. 12 St. as I receive the results of my first HIV test. And now, as though they were there all along, already in my presence, collective trauma defining me, shaping who I am, who I thought I was becoming. Really, I knew nothing, that 13-year-old, that 25-year old in a back room at WonderBar, just surviving. These artifacts were never seen by me in real time, but soon after, somehow, I learned that sex = death, and it froze me. I look at these decades-old documents now and feel them like fresh triggers that open up a terror in my stomach. But the nuance and complexities and newer understandings of the disease that I’m gaining—who was impacted, how its perception was shaped by neglect and erasure, then and now, and how I’m finding evidence of that neglect in the archives I visit, and in my own memory, all of this gives me a way to unlearn some of that terror, to share, to course correct.

Maybe I’ll find more if I get closer to the language that’s slipping away now, if I look for myself over there in the trace of something that evades me. I’m bringing these moments together, out of place, out of time, close enough to touch on the timeline, even though they’ve never met before. I’m stretching out these artifacts, opening up other durations to make them longer (“being long”), so they can touch each other at the edges, so I can touch them and try to make sense of my own queer body traveling through time and space, touching other bodies, moving through like a loose radio signal, echoing back on itself, confounding and liberating all at once. What if I could hold space, a contact zone, for that script on the cover of my father’s menu in 1975 and the gay-porn-gay-cancer magazine in 1981, and the all-caps NYT headline set in Latin Elongated (designed by M. Jean Rochaix for Stephenson Blake & Co. in 1873), and the photograph of me at 13 standing in front of my grandparents’ house, all there together, with some other things too, saturated with memory for me. Maybe there’s a small dark blue Greek-English dictionary with a plastic wrap-around cover, that my father probably got for me when I was 8 or 9 at that Greek store “Prodromidis” on Bouzouki Boulevard (8th Ave.), no longer there, to help me speak his language.

Is there anything of value in these tiny stitches, or am I forcing it all into place? What else am I accessing here, if not intimate typographies? How about this: can I get closer to the language that’s always been there, accompanying me, language that I’ve always already taken with me my entire life. In a queer accounting of time, the language, the fonts, the feelings, the sounds and smells in that photograph—the confusion of all of this—it doesn’t matter if I need to gather them from different corners of the house. I didn’t see the Native or Mandate headlines when I was 13 years old, I’m sure of that, and I’ve never seen the AIDS Memorial Quilt in person, but I’m finding these things now and something’s possible with that, here in this space, in the contact zone. I’m deepening that sense of these worlds that formed me.

Is this a way to learn about design? I wonder. What is this? What do we do with this?

Queer kin

It’s May 8, 2025 and I’m walking around Park Slope, Brooklyn, looking for the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA). I see the planters first—they’re painted purple, white, red, and orange, the colors of the lesbian flag, so this must be it. The LHA has lived in this 19th century townhouse on 14th Street since 1992, purchased entirely through donations—a remarkable achievement that secured its future as an important destination for queer life and research. By the time it got its new home, the archive was already a legendary home-grown institution, organized since the early 1970s out of the living room of its founders Deborah Edel and Joan Nestle on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

I’d made an appointment for a two-hour research session on a Thursday evening; Nina encouraged me to go because she’d seen some Greek publications there when she visited. When I walk in, one of the volunteers asks if I’m looking for anything in particular, so I mention Lesvos—was there anything specifically about the island in the collection? They seemed pleased with the request, smiled, said oh of course, we must, I bet we do. A bit later, they walked over and handed me an archival box labeled “GREECE + CYPRUS Box 1 of 1.” I was looking for queer ancestors, both lesbian and Lesbian, here in the storied Lesbian Herstory Archive, wishing, yearning for some kind of new connection, more information, anything at all to add to the sketchy memories and limited imagery of my own archive, looking to decode these trips to my father’s island in the 70s and 80s before I was fluent in all of my adult languages. What else could I draw into the zone?

In insisting on the value of apparently marginal or ephemeral materials, the collectors of gay and lesbian archives propose that affects—associated with nostalgia, personal memory, fantasy, and trauma—make a document significant. The archive of feelings is both material and immaterial, at once incorporating objects that might not ordinarily be considered archival, and at the same time, resisting documentation because sex and feelings are too personal or ephemeral to leave records. For this reason and others, the archive of feelings lives not just in museums, libraries, and other institutions but in more personal and intimate spaces, and significantly, also within cultural genres.10

In describing the Lesbian Herstory Archives in An Archive of Feelings, Cvetkovich writes that “rather than being a specialized domain for experts, LHA is a welcoming sanctuary;” its domestic interior was once an actual home: “the downstairs living room serves as a comfortable reading room, the copier sits alongside other appliances in the kitchen, the entryway is an exhibit space, and the top floor houses a collective member who lives there on a permanent basis.”11

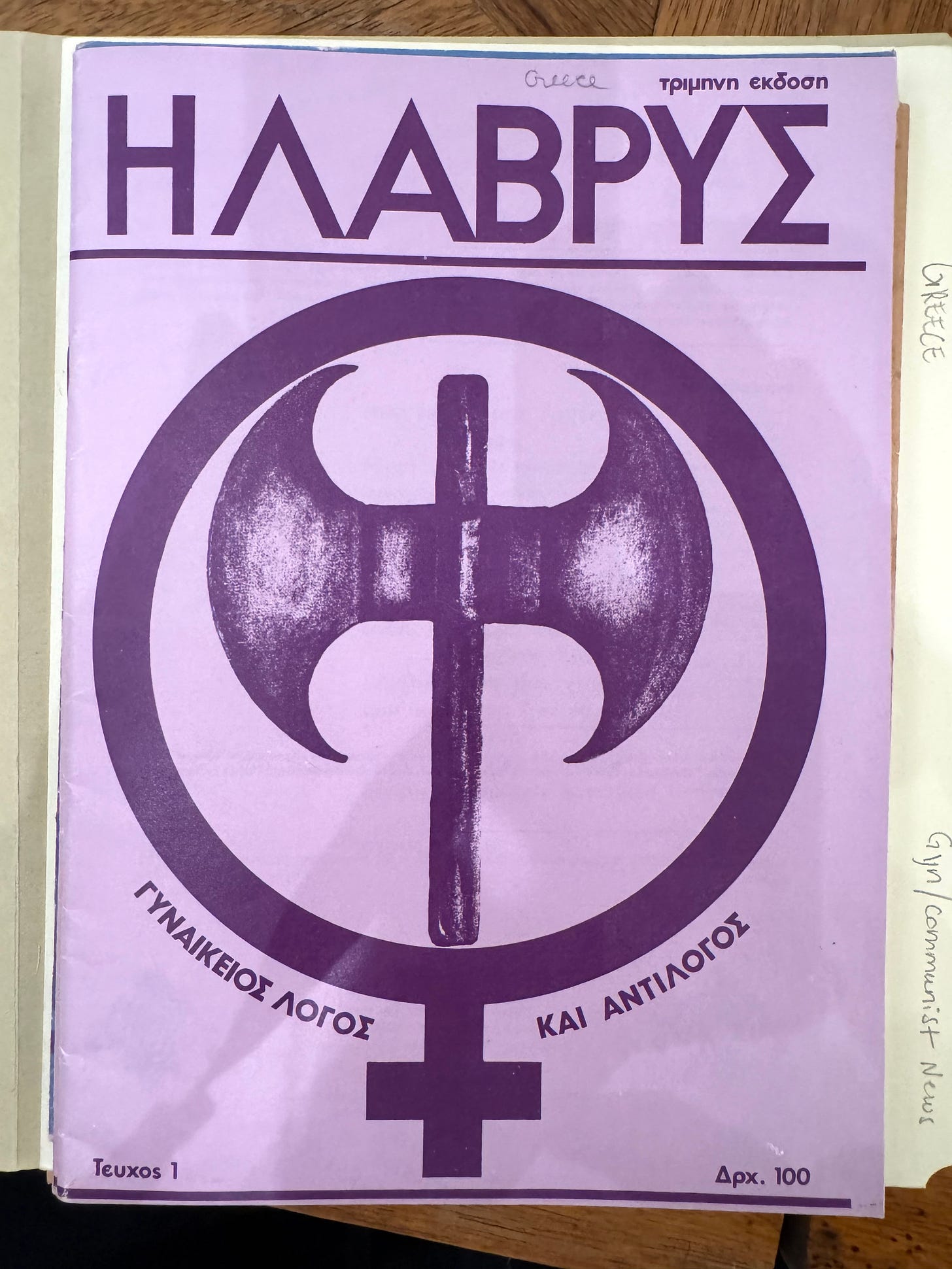

I sit down at the archive’s original dining table, purchased in 1973 when it was still in Deb and Joan’s apartment, and spread the contents of the GREECE + CYPRUS box out in front of me. What I didn’t expect to find inside that box was my own present self, rooted, grounded in place, in a reading room in Brooklyn. Box 1 of 1 contained a small collection of publications from the early Greek gay liberation movement, including the first few issues of ΑΜΦΙ (Amfi), the first gay magazine published in Greece, as well as HΛABPYΣ (Labrys), the first Greek lesbian publication.

Published in 1982, it was discontinued after the third issue, following economic problems and internal disagreements, but for this reason its significance for Greek LGBTIQ+ history is great. The women behind Lavrys were involved with the nascent Greek feminist movement, and also with various communist and leftist groups.12

I open the the first issue of Labrys, and I’m stunned; this is the Greek alphabet doing things I was never able to see as a child, when I struggled to understand what my grandparents were saying to me, and all of the cousins and neighbors and strangers in the village, voices surrounding me with sharp jabs of understanding and alienation. How can an entire alphabet be so intimately familiar, the sight and sound of a language so embodied in my person, so inside my youth, yet somehow so outside my mouth.

I really didn’t know what I was looking for, just feeling my way through, sensing, trying to stay in the contact zone. I turn to page 28 of the first issue of Labrys; it’s a feature dedicated to the status of gay and lesbian rights in the US. Incredibly, this article includes a photograph of a Lesbian Herstory Archives banner being carried by Edel and Mabel Hampton, an activist and early member of the archive, at the 1980 Pride Parade in NYC. The year before Gay Cancer Summer. It’s 2025 and I’m sitting at the LHA dining table with this photograph, published in Greece in 1982, and this is the sensation of time travel, my visitation from the future, of finding myself both grounded at the table and “being long” across decades. Cultures, languages, and sensations criss-crossing and transposed. Scrubbing the photo for details, I recognize the buildings in the background; they’re marching north up Fifth Avenue, the Washington Square Arch just barely visible in the distance. I had watched the NYC Pride Parade right there at that same spot on Fifth Avenue all through the 1990s. And then when I checked on Google Street View, and lined up the view—yes, they’re carrying the banner right at E. 10th St. and Fifth, where I lived from 1996 until 2003. They’re on my corner, 16 years before I got there. I was looking for Greek ancestors, and found my queer kin.

Intimate typographies

Now it’s the morning of June 28, 2025, the 56th anniversary of Stonewall, and I’m back in NYC. I’m walking towards the Stonewall National Monument, the triangle of space bordered by Christopher, Grove, and W. 4th Streets, because I want to see the changes with my own eyes, the malicious deletion of the letters “T” and “Q” from LGBTQ and the removal of the trans flags by the Trump regime, which was reported widely in the news earlier this year. Helpful staff at the Stonewall National Monument Visitors Center, funded by Google and Disney and Donatella Versace and AARP (but not the federal government), tell me that the local park rangers have been very supportive and that the most egregious changes were on the National Park Service website, where letters and language were sloppily removed and Marsha P. Johnson’s page and other content was deleted. I cross the street and look at the information panels on the wrought-iron fence surrounding Christopher Park, decorated with dozens of rainbow flags by the park rangers for Pride. Trans flags, banned by the Trump regime, were everywhere, defiantly added by visitors. A “fence exhibit” displays photographs and QR codes that lead to the modified website.

Remarkably, some of the panels displaying black-and-white photographic portraits of our community’s trans ancestors have been annotated by visitors with adhesive letters, a noble act of caretaking, a kind of queer typographic correction (and connection), an inscribing, however temporary, to identify and proclaim and sustain. In the annotations, I’m reminded that these images are saturated with memory for me, even though I never knew Zazu Nova, Sylvia Rivera, or Marsha P. Johnson when they were alive. Saturated with memory for us. The act of spelling out their names in public, identifying them by rubbing these notes down on National Park Service panels, claiming their powerful presence, calling them up into the park. The sticky letterforms remind me of Letraset typography of the 1970s, typography on portable sheets that could be rubbed down onto any surface, and in that moment I’m thankful for this, that rubbing can be writing, anywhere we want. I trace over the sticker-letters in my photos now to re-inscribe and re-transmit these messages to a different place, over different networks, to point to the power of intimate histories that get written in public, and the beautiful forms that liberated language can take when traveling across time and space. A small effort to extend the life of these lines.

ZAZU NOVA ALWAYS BE HERE

SYLVIA WILL ALWAYS BE HERE

MARSHA P JOHNSON IS HERE

These stickers in the West Village in 2025 are ephemeral love letters, unusual traces written in public, barely surviving, but they do. I’m looking at them now, and the memorial quilt panel sewn for Katrina Haslip, and the archive’s banner in the 1980 NYC Pride Parade, headlines from 1981, a Greek lesbian publication from 1982. I’m trying to locate myself on this overflowing timeline that opens up and reveals new narratives, crucial stories that I need, that I’m craving. I grab on. It’s my father’s journey from Lesvos in search of something, a menu in the basement, an informal typeface that felt just right, and my own search for fluency, in all of my languages. These are the queer design objects of my childhood, even as I see some of them now for the first time. These are my design lessons; I’m holding them close by at 7 and 13 and 23, now at 57, claiming my own quantum queer history that holds all of these moments together, some kind of energy that spans decades. As I look back to move forward, these narratives continue, all of these edges touching on the timeline, revealing other kinds of design histories, sometimes random but always specific, to be claimed and shared. These proximity artifacts stretch out along multiple timelines, long and steady, writing and re-writing themselves. These are some, but not all, of my intimate typographies.

The title of the workshop is taken from a line in Marika Cifor’s “Presence, Absence, and Victoria’s Hair: Examining Affect and Embodiment in Trans Archives,” Transgender Studies Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 4 (2015), p. 648.

Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, Introduction, Duke University Press, 2003, p.7.

Ibid, p.8.

Ted Kerr, “39 Years Later, The New York Times’ 1981 ‘Gay Cancer’ Continues to Distort Early AIDS History,” The Body, July 2, 2020.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, New York, NY, Farrar ,Straus and Giroux, 2021. p.241.

Kerr, 2020.

Mireya Navarro, “Conversations: Katrina Haslip; An AIDS Activist Who Helped Women Get Help Earlier,” New York Times, November 15, 1992.

Cvetkovich, 2003, p.243–244.

Ibid, p.241.

“Feminism and Lesbian Politics,” Glasgow Women’s Library, webpage: https://womenslibrary.org.uk/explore-our-collections/lgbtq-collections-online-resource/feminism-and-lesbian-politics/

"I didn’t yet speak any of the languages—Greek, queer history, gay desire—that would go on to shape my life." I so feel for your young self! No wonder exploring language and lettering defined you, and continues to define you.

What a lovely post. Thank you. Let me know if you ever come by Athens! Also, are you familiar with Kyklada Press (https://kyklada.press/)? If not, I believe you'll enjoy many of their titles.