I’m thinking about the printed web again. It’s been years! This time, I’m focusing specifically on “survival printouts”—the act of printing out at risk material from the internet to save it. When it comes to survival, paper printouts persist.

A paper printout of internet material is such a strange mix of conditions. Because of its hybrid media status—first as digital material that circulated online, and then on physical paper—a printout possesses digital and analog qualities simultaneously. A paper printout of at risk internet material is different from other kinds of printing because it points directly to the act of printing itself as a moment of decision-making and survival. Printouts don’t involve print professionals (in the traditional sense); they happen because someone close to the digital material makes a decision to “be safe” or “make a backup.” When they “print it out” with materials and equipment at hand, the internet material enters a new dimension. It takes on a more stable condition, where it can be safely moved, stored, shared. The greatest affordance of a printout moment is that it gives the material a greater chance of survival across time and space.

I just had a deeply moving week in California visiting two precious examples of early-internet (pre-web) paper printouts that continue to persist for decades. These are printouts related to specific moments in queer history that would have been lost, had the decision to print them out not been made. I learned about these documents online, and suspected they might have a particularly emotional charge or aura about them in person, given their special contexts. I wanted a chance to encounter their material trajectory through time, and to examine them closely as physical evidence of queer life. I wasn’t prepared! These experiences were extraordinary. I’ll write about one of them here, and the other in a subsequent post.

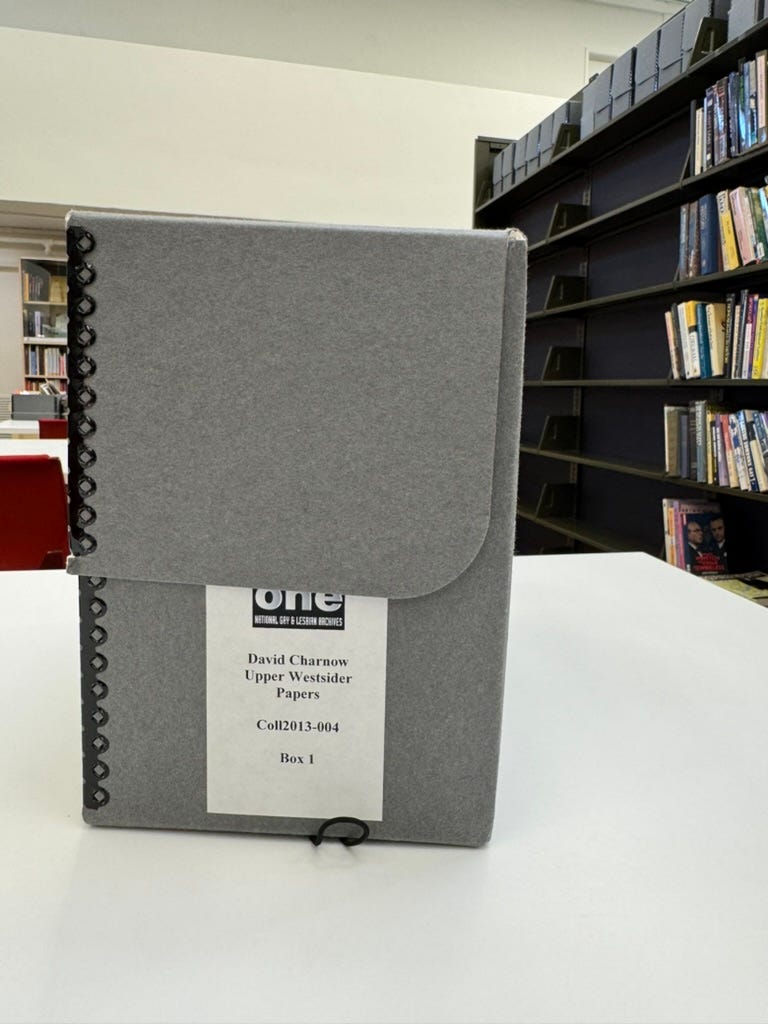

At the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC in Los Angeles I examined an artifact labeled “David Charnow Upper Westsider papers, 1987-1990,” also known as the SURVIVORS printout. Inside a cardboard box are 12 folders containing more than a thousand loose sheets of letter-sized computer paper printouts. The story of the SURVIVORS printout was beautifully documented and analyzed in this text by Kathryn Brewster and Bo Ruberg in 2020, which is where I first learned about it. The authors identify several important themes within the content, and of the printout itself as a media artifact, which I won’t repeat here; rather, I’ll focus on my own experience of the printout in more affective and embodied terms—“queer material in queer hands,” as stated by Ben Power elsewhere1—and how the SURVIVORS printout is a stunning example of “survival by sharing.”

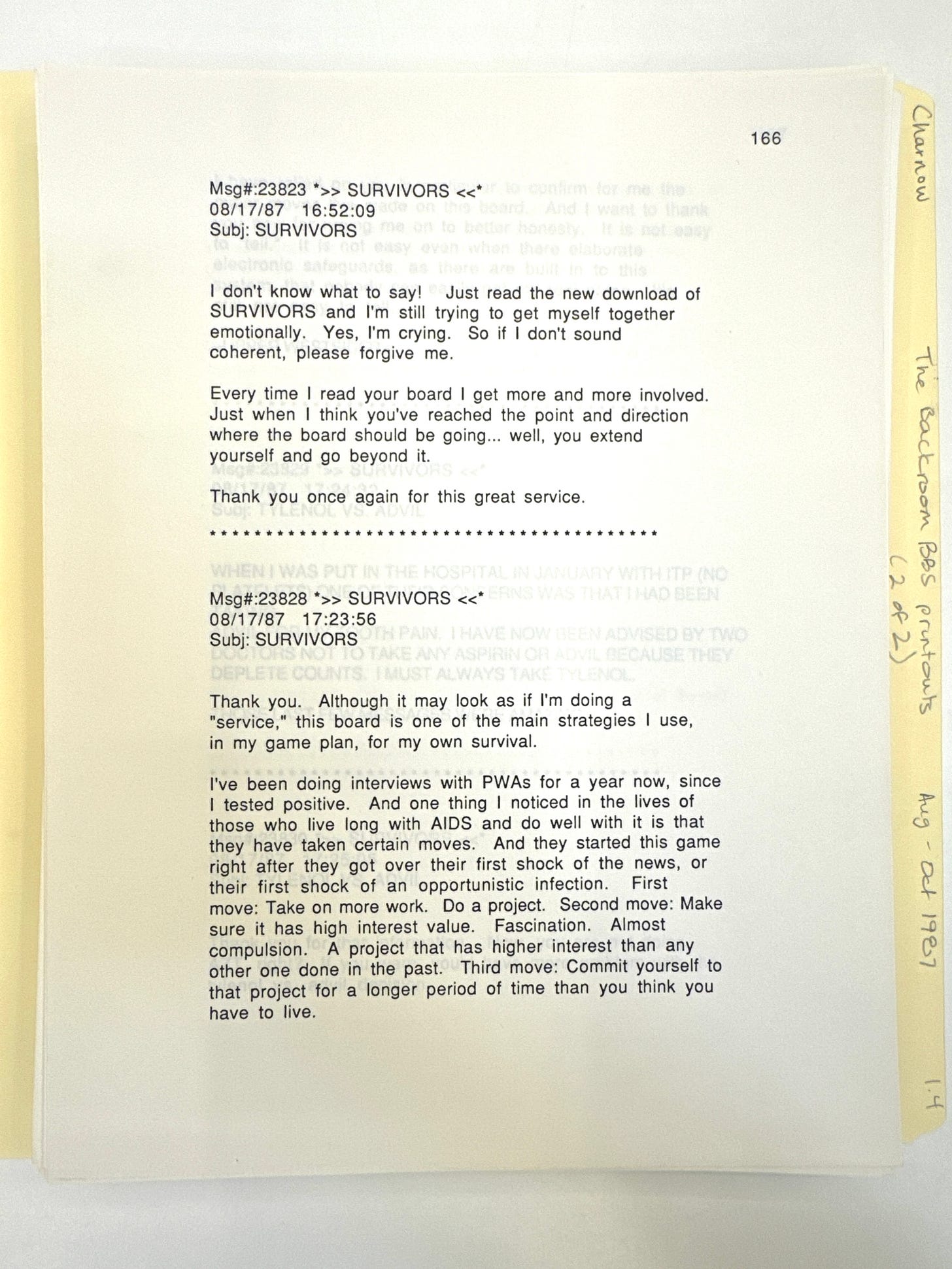

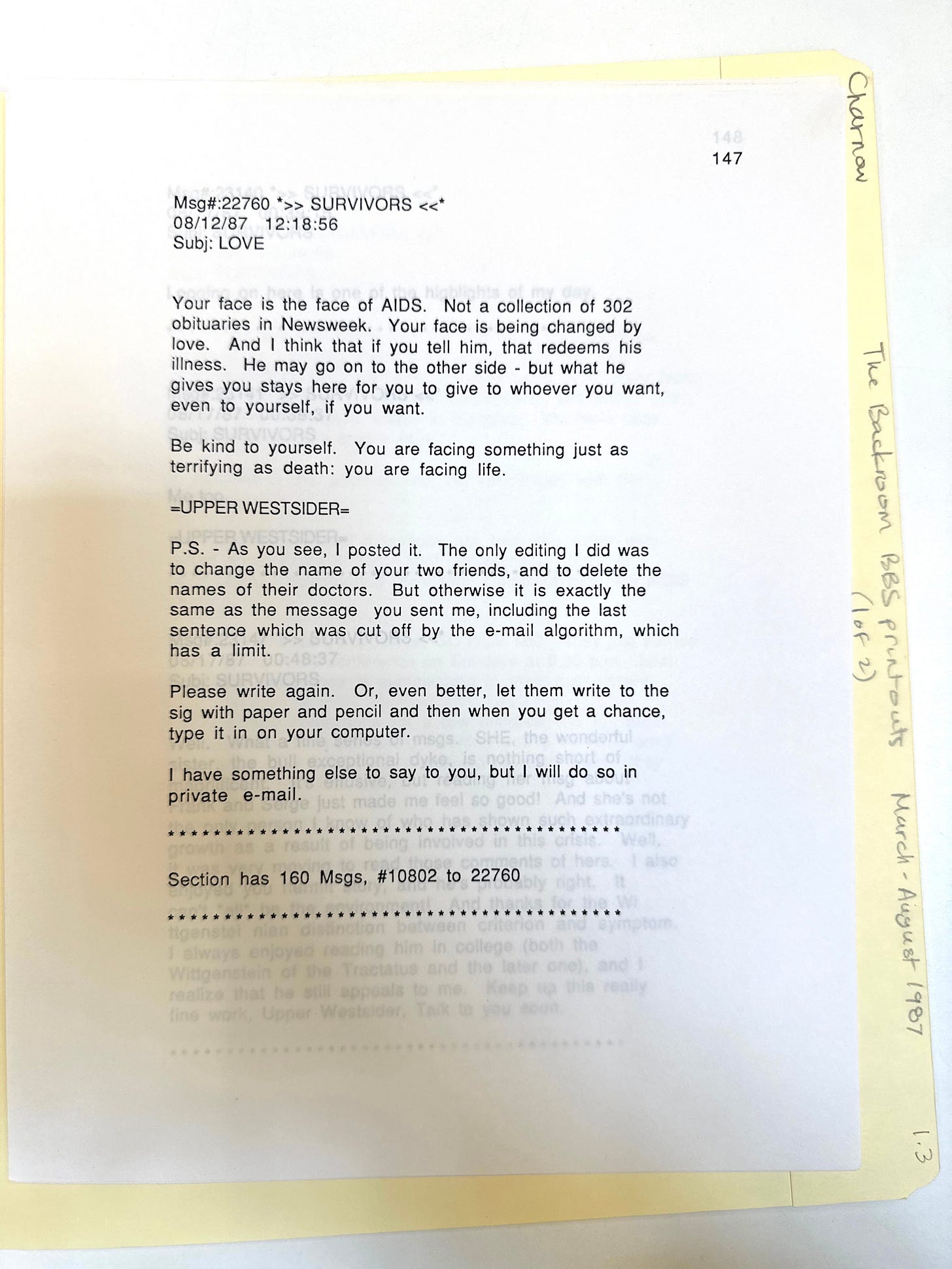

The SURVIVORS printout documents an early online message board for people with HIV/AIDS that was a section of The Backroom, a gay digital bulletin board service (BBS). SURVIVORS was created by David Charnow (1942–1990) in 1987, while he was completing his Ph.D. at Columbia University. Charnow learned that he was HIV positive just as he started SURVIVORS, and documented his struggles in his own posts, signed with his handle =UPPER WESTSIDER= (in the future I’ll write about this handle as a powerful example of queer typography). His posts were numerous and mixed in with writing from others who came to the message board to search for and offer information, guidance, and support. Charnow ran SURVIVORS as a queer survival network until July 1990, when he passed away from AIDS-related illnesses. He made a complete printout of all of the posts one month before he died. The SURVIVORS printout was donated to the ONE Archives by Susan Charnow Richards in 2000, according to the finding aid. There’s a copy of the printout at The Center in NYC as well.

After spending seven hours with the printout, I left the archive and just kind of broke down in the car. The emotional weight of the experience was extreme; it was a lot to process and I’m going to return to Los Angeles to spend more time with it. The content itself is deeply moving and powerful in ways that would be expected (interconnected stories about illness, dying, loss), but I think I was responding to something else as well. It had to do with the ephemerality of the artifact itself (loose papers, folders, a box), its minimal presence, its barely-there materiality—all of this in contrast with the enormity of the world contained in the box. I was hit with a sharp awareness of time that I sensed as a loss in my own body. It was about being in proximity with this box, and it had to do with my own being and my own survival.

It was a realization that each of the posts contained in the SURVIVORS printout was a direct conduit to someone, all of these lives engaged and entangled with each other over a digital network that no longer exists, and that the authors’ actions at the keyboard—making these posts—is all that remains. This is what persists: the box with a thousand sheets of paper, documenting their queer acts of typing, which I was able to access only as a direct result of Charnow’s decision to print, and my access to this archive. I felt connected to him and his decision, entangled through this fragile trajectory of papers ending up in this box at the ONE Archives. Within the hybrid digital/analog condition of the SURVIVORS printout as a media archeology, I found something else—a more emotionally fraught hybrid condition of being and existence, of being both there and not there. Handling the evidence with my own hands was a full, connected experience that I felt deeply in my body, as it positioned me directly in front of major gaps in the timeline: the loss of lives and histories stopped short, neglected, forgotten, of course, but also—the loss of my own experience of that crisis. I was alive throughout the HIV/AIDS crisis but “unconscious in the street,” frightened, alone, and turning away from it as part of my own survival. I’m reckoning with that now.

Marika Cifor writes that “archives offer the possibility of survival,” in describing an encounter with a single human hair in an archive during their own research, likely belonging to Victoria Schneider, a trans woman, sex worker, and activist.2 Such an encounter “closes some of the distance between objects and the lives they represent, bringing together bodies to build identities, stories, and futures for themselves, while maintaining space for possibility and keeping subjects in time differently.”3 Cifor writes that the stakes of such an embrace are high, and that the central question for archives is “how the past that emerges from them ‘can potentially produce a revelatory historical conscious of the present’ that is so desperately needed.”4

Describing such an encounter as an embrace resonates with me; my embrace in the ONE Archives (did I embrace the SURVIVORS, or did they embrace me?) was personal, intimate, and embodied. My entanglement has everything to do with my own timeline: I was born in 1968 and alive at the time of the SURVIVORS discussion group, and my own survival during the past 34 years. My connection to Charnow and all of the participants in the SURVIVORS discussion group as queer ancestors grounds me in the present, and guides me forward in time, towards the commitments I need to make, to grow through their stories, to share more, to create new evidence, to create openings for future entanglements. Am I doing enough? Survival networks are everywhere today, in the ruins of bombed neighborhoods, in queer manifestos of survival posted on Instagram, in stories written here on Substack, on Telegram and Discord servers. I’m overwhelmed with the possibilities for queer archive work, while being painfully aware of how challenging it is (and at times questionable, ethically) to make queer material more (or less) visible, more (or less) legible. I’m committed to the work, but I suspect it’s never-ending and mainly, mostly, an unfulfilled task.

This return to the printout makes me think hard about Library of the Printed Web, a publishing and curatorial project that I began in 2012, ending somewhat abruptly when it was acquired by MoMA Library in 2017. Outside of the aesthetic allure of the project, I failed to understand the political qualities of the printed web at the time, and the urgency of at risk internet printouts (I explored at risk printouts a bit with a few later projects, like Thank you for your interest in this subject (2017) and Steve, Harvey and Matt, (2018)). I was so focused on documenting artistic appropriation, publishing, and printing practices in the early years of the 21st century that I neglected to see how printing out the internet was actually a much older practice, one that can have enormous implications for how we understand the interconnected politics and cultures of the early internet, queer history, and movements towards liberation.

An even earlier example of a liberatory printout—perhaps the first one—is the Community Memory printout at the archive of the Computer History Museum, in Fremont, California. I was able to visit that one, too, and I’ll write about it in my next post.

K. J. Rawson, “Archival Justice: An Interview with Ben Power Alwin,”, Radical History Review, Issue 122 (May 2015).

Marika Cifor, “Presence, Absence, and Victoria’s Hair: Examining Affect and Embodiment in Trans Archives,” Transgender Studies Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 4 (2015), p. 648.

Ibid, 648.

Ibid, 648, referencing Roger Hallas, “Queer AIDS Media and the Question of the Archive,” (2010).