Keyboard Problem

Looking for queer +ypography

I’m back in Los Angeles for a more extended, multi-week visit to the One Archives, as I begin research and writing for a book on queer typography (forthcoming fall 2026). I spent a day here back in August, and wrote about the SURVIVORS printout, an important piece of media archeology in the One’s collection, focusing more on the embodied (or maybe even out-of-body) entanglement I experienced when confronting the ephemerality of this particular artifact in the archive. In all of its power and fragility, the folders, box, and one thousand loose sheets of paper that make up the SURVIVORS printout warp queer time and position me directly in front of major gaps and voids in my own timeline, and I’m still processing that experience.

I want to keep thinking and writing about the SURVIVORS printout, as a way to explore and understand it more deeply. Specifically, there was a page that stood out from all of the others, for a reason that goes beyond the obvious emotional content of the author’s message.

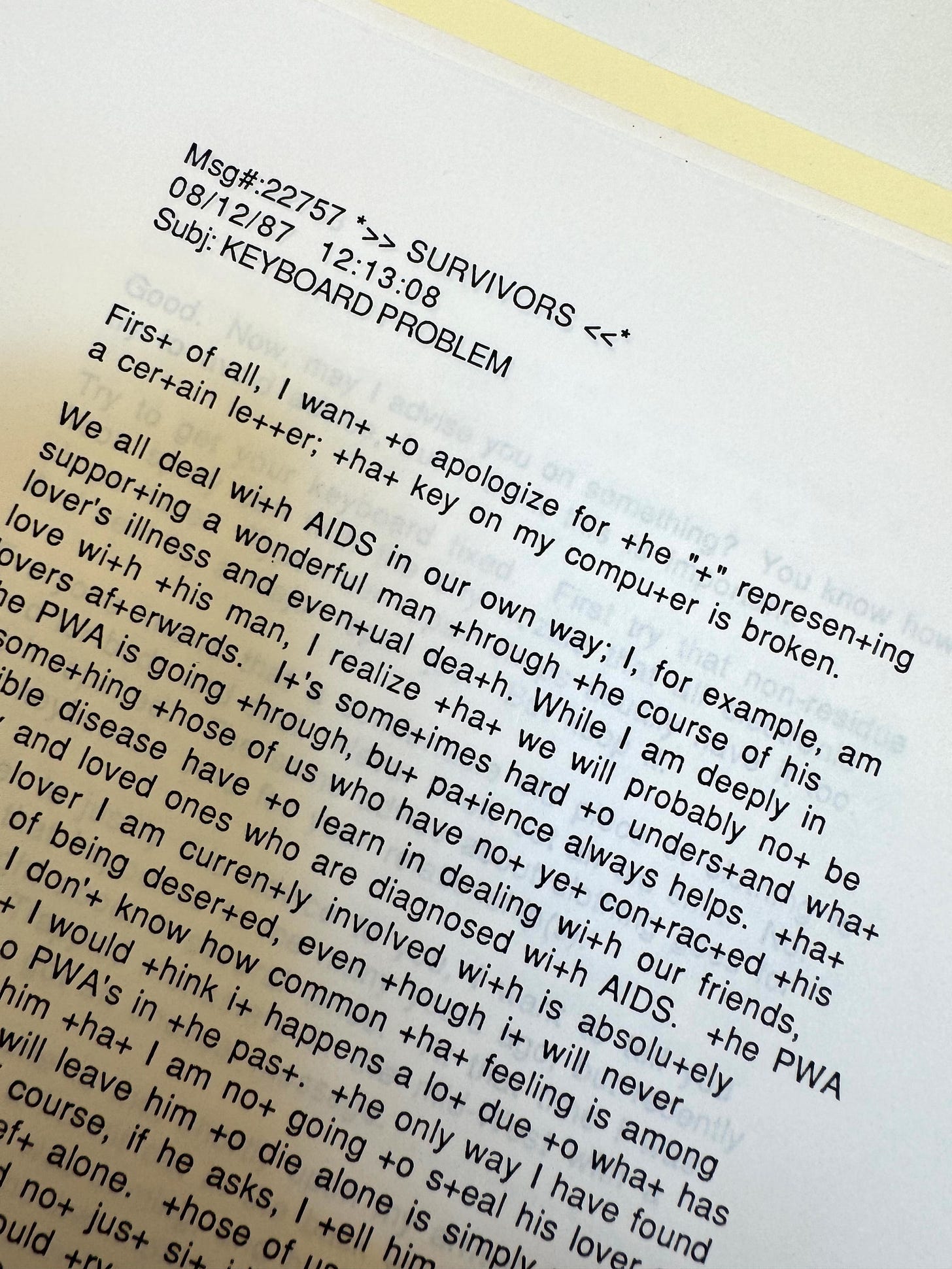

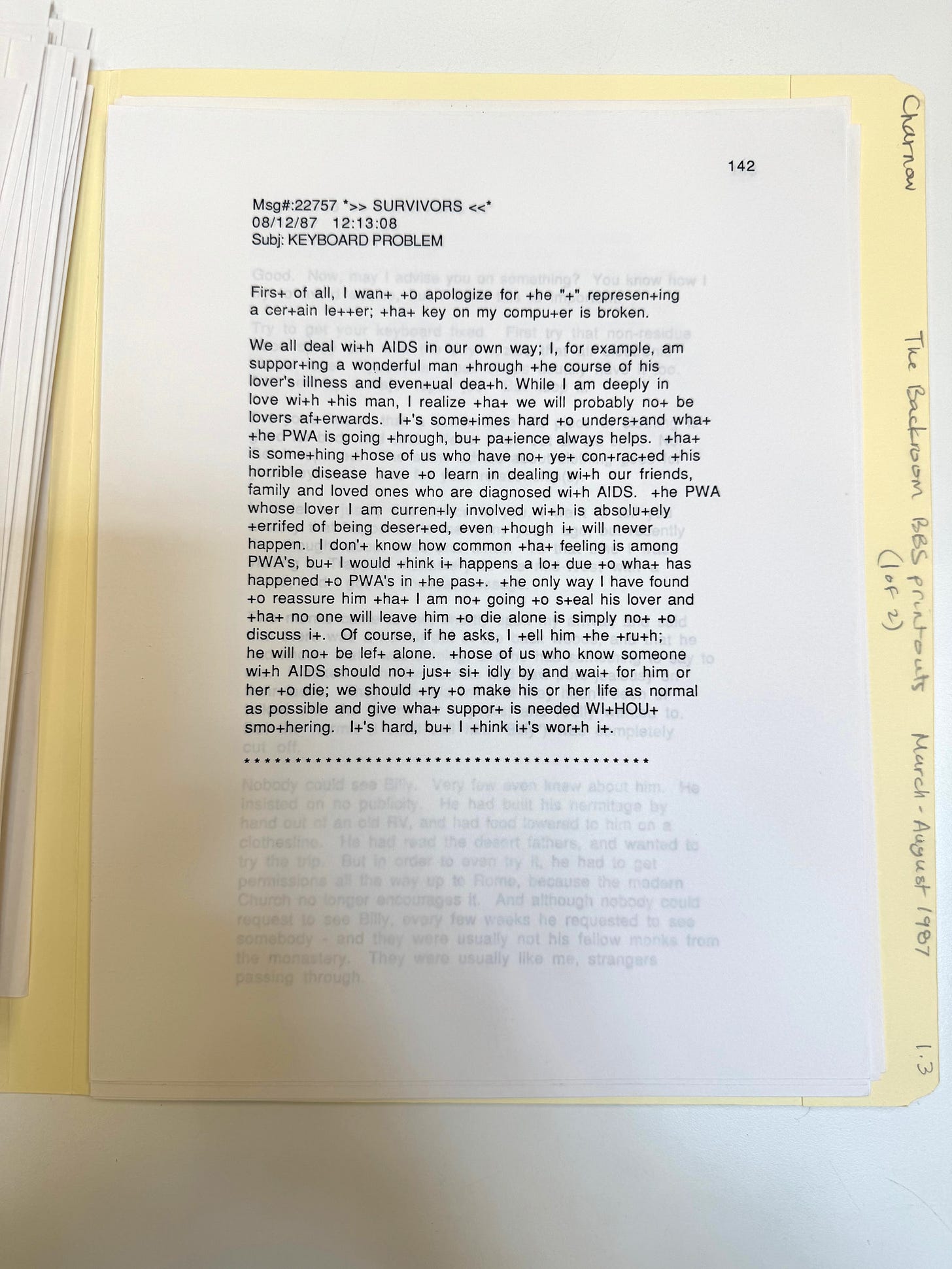

This is message #22757, dated 08/12/87 at 12:13:08, Subj: KEYBOARD PROBLEM. Its author isn’t identified, nor is their gender, age, or any other traits; they wrote the post to share their experience of caring for two people: one who was ill with HIV/AIDS, and that person’s partner and primary caregiver. What’s striking though is that the author begins the post with an apology about their keyboard.

Firs+ of all, I wan+ +o apologize for +he “+” represen+ing a cer+ain le++er; +ha+ key on my compu+er is broken.

What an incredible example of queer typography!

I see it this way for a few reasons that go beyond the obvious context at hand. And that context should be noted: I found this page within the largest LGBTQIA+ archive in the world, and the post was written in 1987, during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The original author’s brief message provides insight into the urgent care and support that was happening as communities were struggling with illness, negligence, and death. Without question, it’s a queer story and the printout enables us to locate this author in the otherwise sparse and confusing timeline(s) of queer history.

It’s the author’s opening line that brings this page of writing into another realm, as they apologize for the “keyboard problem” identified in the subject line. The letter “T” on their keyboard doesn’t work, so they’ve decided to substitute “+” for “T” in order to get their message across, and this is remarkable. Faced with a malfunction that creates a constraint, the “+” is a simple typographic hack. They decided to use one keystroke as a substitute for another (broken) one; more accurately, it’s a code, or a cipher, that functions as a workaround. The reader easily understands how to decode the message because it only involves one letter and the forms are similar: the “+” looks like a lowercase “T.”

In fact, the author could have used any other letter or symbol, and the message would still be readable. They could have even left out all of the Ts entirely. At what point does language completely break down? Any one of these solutions, including the “+” substitution, introduces friction and s l o w s down the reading experience. The slower experience asks more from the reader—more consideration, more time, more patience—and this is echoed in the content of the message itself, which is about dealing “wi+h AIDS in our own way,” about the terror of facing death alone, and about the value of standing by for unconditional support.

John Cage experimented with the removal and eventual breakdown (liberation?) of language in 1974 with Empty Words, a book and spoken performance that gradually eliminated sentences, phrases, words, and syllables from Thoreau’s journals, until the language was “demilitarized.” Could a move like the “+” substitution in the KEYBOARD PROBLEM post be considered “demilitarized” in any way? If we consider queer acts of typing that move away from perfect legibility towards a more poetic place—less regulated, towards “other legibilities”—then yes, I think so.

The decision by the author to substitute a plus/positive sign for the broken T takes this simple substitution into a more poetic dimension because this is also the symbol that’s added to the letters “HIV” in order to designate someone’s seropositive status (HIV+). The “+” indicates that the HIV virus is detectable in the body (a presence, a surplus). There’s also this: that the HIV virus attaches itself to T cells and causes them to die, and the decreasing T cell count is what eventually leads to an autoimmune crisis in the body (AIDS), and death. In the KEYBOARD PROBLEM post, it’s the author’s letter T that is broken, replaced by the positive sign. The author of the post, faced with a keyboard crisis, made the creative decision to hack their tool with a modified alphabet, which introduces friction to the reading experience. The result is compromised, not perfect, but absolutely readable. The post contains 104 “+” positive signs that read as if a filter has been overlaid on top of the language; the text has something more, it takes on a new “texture,” but it’s still legible. The author negotiates between the tool, the language, and the forum (its audience and network of readers), to produce a new kind of slower typing/writing. I see this as a queer act of typing/writing, which requires a new kind of slower, queer read—for the reader, there’s no avoiding it.

Is the queer read imposed here a broken one? Is the transformed text an actual problem for the reader? I would argue that by queerly typing the text in this way, the author has instead created a surplus. There is an abundance of love and care that is expressed in the KEYBOARD PROBLEM post on multiple levels, and this abundance is clearly legible. As a reader, I understand their modification in order to get this message across as a surplus of meaning and language, not a problem or a lack.

And the actual font is irrelevant! It’s all about the typing. The hack can transfer to any computer user on the network, and can be output by any printer. It doesn’t depend on any specific technology or platform. The abundance is transferable, flexible, and easily adaptable.

Was the author thinking about T cells and seropositive status when they made the substitution? Were they being clever? I doubt it, but that’s totally irrelevant. The surplus is there now, as it was then, when this message was read on all of the screens of the readers of the SURVIVORS forum, and when it was printed out. It’s these ideas—

a focus on context;

the hacking of language;

the creation of meaningful codes;

modified alphabets;

other legibilities;

care for the reader;

accessibility;

transferability;

new acts of typing, writing, and reading;

a surplus of texture, friction, meaning, and language—

that I’m starting to look for as I sketch out this book on queer typography. I’m grateful to have found this remarkable example, which opens a door to so much more.

But I’m even more grateful for these ancestors: the anonymous author of KEYBOARD PROBLEM, and David Charnow, who printed the SURVIVORS posts in 1990, just one month before his death from AIDS-related illnesses. Their decisions warp queer time and enable us to become entangled in the archive, in their lives across time and space, and to reposition our own bodies in relation to queer histories and futures. There was no way for them to know what would happen next, in their expressions of care, in their simple acts of typing and printing, in the total uncertainty of that moment. “The question of the archive is thus in the end not whether it succeeds in preserving the past from oblivion but how the past that eventually emerges from it can potentially produce a revelatory historical consciousness of our present.”1

Roger Hallas, “Queer AIDS Media and the Question of the Archive,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 16, no. 3, 431-435 (2010).

Hi there Paul,

I was a member of the Backroom BBS and a very close friend to Upper Westsider, David Charnow who ran the SIg called Survivors. I also wrote stories in that sig about my friend dying.

If you want any information on Survivors and David who ran it, please contact me.

Reading this on the plane after presenting my book to the public for the first time this weekend & although the subject matter couldn’t be more distant, the overlaps of the research process, story telling, memory sharing & life remembering is palatable. That Hallas quote feels like a mantra & guiding light of my work. Thank you Paul!